Post by grrraaahhh on Nov 10, 2010 19:25:12 GMT -9

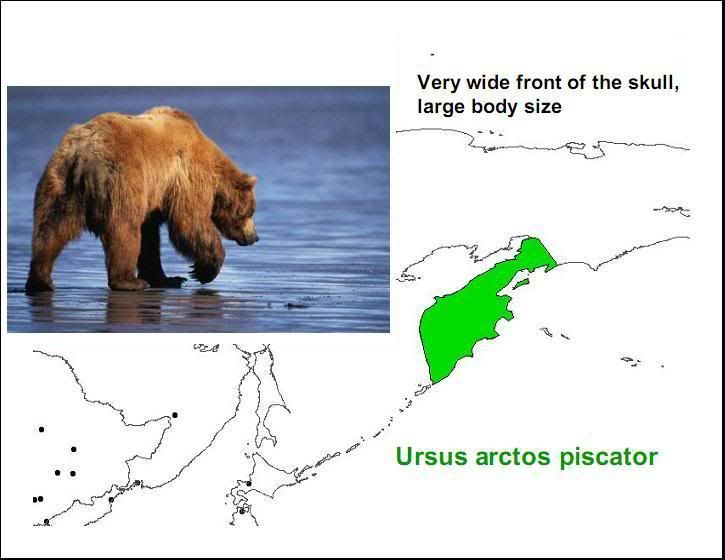

(U.) a. piscator of Pucheran, 1855 - Kamchatka brown bear

Ursus of arctos of kamtschatica of middendorff, 1851: 74 (March, the reprint), 80 (June, periodical) (Kamchatka, on [tavtonimii]) (nom. nudum) - U. piscator of pucheran, 1855: 392 (Petropavlovsk, the south of Kamchatka; the holotype: effigy, MNHN 2001-357, ad, it is studied; is depicted - du Petit-Thouars, 1864: PI. 4 as Ursus of arctos L.,. du Kamtschatka).

Photo credits: Seryodkin, I.V.

Distribution & Population. Kamchatka, north of Kuril & Paramushir Islands. Historically bears were very numerous in Kamchatka. According to Ostroumov (1968), the highest population densities were observed in upper and middle river streams. The total number in Kamchatka was estimated as 18,000-22,000 bears. By the late 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s two-fold depression in number has been widely recognized, however the range did not experience any changes. Dunishenko (1987) summarized the results of censusing conducted in game areas in 1968-1969 on approximately 53% of the region. About 7800 bears were counted with the average density of 0.32 per 1000 ha (maximum 1 per 1000 ha). Extrapolation of the data on the whole Kamchatka area came to 12,000-14,000 individuals. Aerial censusing showed 8,000-10,000 bears living on the peninsula (Koshcheev, 1991). Until now bears are resident throughout Kamchatka, having only slightly damaged habitats - despite their over harvesting.

Pelage. Based on more than 400 visual encounters in 1985-1989 it can be established that in southern Kamchatka 14% of bears were light brown or ocher colored, 31% were reddish, brownish and bronze and 55% were actually brown, dark brown or black.

Ecology. The area of Kamchatka is 463,900 sq. km. The mountainous relief determines the stratification of vegetation. Birch forests are spread from the river valleys up to 600-700 m a.s.l. Trailing forms of alder and Siberian pine occur from the tundra lowlands to 1,000-1,300 m a.s.l., forming the zone above the birch forests. Mountain tundra occupies the zone above the trailing alder and Siberian pine up to 1,600-1,800 m a.s.l. At elevations higher than 1,600-1,800 m a.s.l. one can observe stony scatterings and glaciers. Coniferous forests can be found along Kamchatka river mid-stream and at the northern part of the peninsula (Revenko 1993).

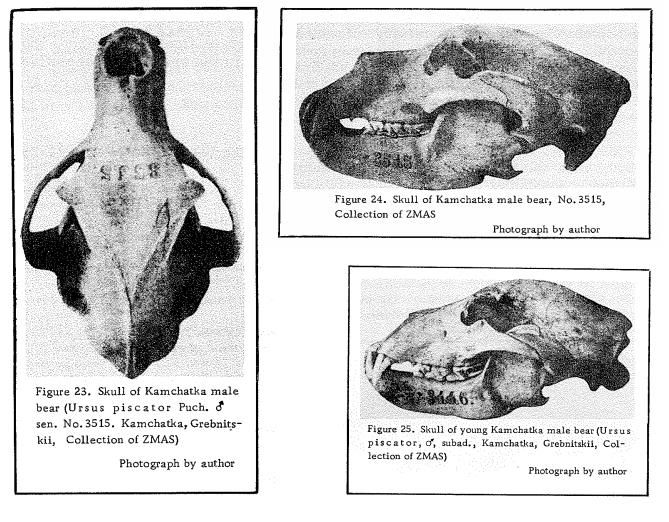

Trans-Pacific ancestry between the brown bears of Asia & North America is recognized. A relationship in skull morphology between the giant size brown bears was observed by Ernest Schwarz nearly three quarters of century ago. Regarding their early taxonomy, Schwarz pointed out how earlier Zoologists Alexander Theodor Von Middendorff (1853) and Clinton Hart Merriam (1896) were aware of a close relationship between the giant bears of northeastern Asia and those of northwestern North America. Schwarz would add that careful examination of the Kodiak bear leaves no doubt that the difference between Ursus beringianus beringianus and Middendorff is only sub specific (Schwarz 1940). Bjorn Kurten later advanced the hypothesis of a trans-beringia ancestry between the bears of Kodiak Island and Kamchatka (Kurten 1973).

In contemporary times, F. B. Chernyavskii & M. A. Krechmar echo Schwarz describing how the large and broad skulls of the Kamchatka brown bears are similar to those in the bear population (U. a. middendorffi), inhabiting Kodiak and Afognak Islands. U. a. beringianus has common features with U. a. dalii from Alaska Peninsula. The authors also affirm an earlier trans-beringia migration of the Siberian Ursus arctos form to North America (Chernyavskii, Krechmar 2003).

Incorporating the materials of Robert L. Rausch, both Chernyavskii and Krechmar support a trans-Pacific relationship between the size and diet of brown bears. To translate and paraphrase the authors: in this regard, there is some reason to believe that in accordance with the hypothesis of (Rausch, R. 1963) the large bears in southern Alaska and British Columbia, there occurs the proliferation of large forms U.arctos on the Kamchatka Peninsula, Sakhalin and Amur region which is also associated with its habitat in these areas are many populations of anadromous Pacific salmon - genus Oncorhynchus not only in the overlapping ranges of salmon and large subspecies of brown bear at the present time, but especially of trophic relationships that evolved between the four-legged predators and salmon on the Pacific coast of Beringia in the individual stages of the Late Pleistocene. These coastal bears are of large size and wide skulls that has been associated with use of spawning Onchorhynchus Pacific salmon (Kurten 1973). More specifically, bears with the relatively widest zygomatic arch, inhabiting Kamchatka and Kodiak Island, share their ranges with spawning grounds of the two largest species of salmon (sockeye [O. Nerka] and Chinook O.Tshawytscha]). There is little doubt that the first brown bears inhabiting coastal regions of the Okhotsk and Bering Seas during the Wisconsin also had access to anadromous salmon" (Cherniavskii, Krechmar, 2001).

In the modern era, mtDNA testing supports a genetic relationship between bears of Kamchatka and Kodiak island and the Alaska peninsula (Talbot & Shields 1996).

Above: iconic rendition of the coal brown peninsula giant.

Diet. U.a.piscator nutrition in the region depends on three main items, namely spawning salmon species, dwarf Siberian pine nuts and berries (Averin, 1948). According to Mattson's opinion (pers.comm.), Kamchatka is a unique area in the brown bear range where all these three are abundant. Despite not being the main food, the marine animals washed in along the coast provide bears with rich food in early spring and summer. Mainly these are whales, seals, mollusks, fish, birds and marine plants. Bears also prey on sea otters in Lopatka Cape (Koshcheev, 1989).

When the spawning season starts bears will concentrate near the rivers. The individual home ranges during that time overlap and complex social relationships are developed in the population. If there is a good crop of dwarf Siberian pine nuts, bears leave the spawning sites even if salmon are still there. These nuts can remain over the winter period and provide bears with valuable food in poor spring conditions.

After the extraction of salmon, bears will usually transport their production away from the shoreline (73% of cases) for consumption. Sometimes bears will carry extracted salmon as far as 40-50 m (by the lower reaches of the streams of rivers in August 2004 g. to 27 m, usually 1-7 m, average 2.6 m, n= 19). Similarly, movement of salmon production behavior outside of its water sources to nearby trees and bushes is often observed with young and smaller bears. Similar behavior by bears have been recorded in the uneasy company of humans. Physical consumption of salmon depends on the natural river bedding; for example, with respect to the large sandy - pebble islands or the scythes among the river; bears regularly eat salmon on the sandy or pebble ridden shores. On the elevated shore, bears frequently depart nearer to the timber line areas. Leftover salmon are regularly eaten by other animals most notably birds (Lobkov 2006).

Bears start eating the rowan berries in mid-July, 1-1.5 months before their ripening. Blackberry and blueberry crops are usually stable in the tundra zone and bears concentrate on their stands in August and September.

In the spring-summer period, the bear's diet is vegetative and their distribution is uniform from the coast and flood-plains up to the sub alpine zone. From mid-July, when salmon come for spawning and berries start ripening bears move to the flood-plains, lowlands and tundra. Latter ripening of rowan and dwarf Siberian pine coaxes bears back to the middle mountain zone although they still visit the habitats with spawning salmon and berries.

Depending on the availability of the primary food items bears can travel up to 80-100 km. The probability of a poor crop of all the three main food items is very low and 'shatuns', or non-hibernating bears are found very rarely. However, sometimes it may occur and even the pestilence of bears has been observed. According to Vereschagin (1971) this happened in Avacha River valley in 1923-1924, in Ust-Kamchatka district in 1940-1941 and in many districts in 1954-1955 and in 1958-1959. In the autumn of 1985, the crops of berries and dwarf Siberian pine nuts in western Kamchatka were very poor and the spawning activity of salmon low. Many bears switched to preying on mice and sea otters, and damaged cabins. Several cases of cannibalism and attacks against humans were also registered (Koshcheev, Ostanin, 1986). In 2008, hungry Kamchatka brown bears trapped a group of geologists killing two scientists (Los Angeles Times, 2008).

Size and mass of Kamchatka subtype of brown bear (U a. piscator of Pucheran, 1855) one of the largest ground-based bear predators and under optimal conditions the maximum fixed weight of a male of Kamchatka bear registers 600 kg, the average weight 350-450 kg are confirmed data and before the autumn period the weight of record specimens have exceeded 700 kg (Gordienko, 2005).

Behavior & Activity. Depending on the latitude, autumn food availability and dynamics of snow cover as well as oh the sex, age and reproductive status of a particular animal, bears in Kamchatka are active 5-7 months a year. As a rule, pregnant females and females with cubs go to the dens 2-3 weeks earlier and come out 3—4 weeks later than single sub adults and adults and females with older cubs. Some bears, commonly adult males, stay at the spawning sites until late December. The earliest dates of bears leaving their dens (early April) are observed in the areas with extensive volcanic activity.

Mating. During the breeding season and in early spring bears form breeding groups. For example, in Kuril Lake drainage at the 22nd of April, 1990, there was observed 67 bears on an area of 40 sq.km including 14 breeding pairs. The elements of breeding behavior are observed in mature animals immediately after leaving the dens. Males are looking for the tracks of females and follow them until their meeting. Observation data reveal up to 30% of breeding groups consisting of a female and 2 males. Copulation occurs 2-3 weeks after the group is formed, usually in May or June. Even though the group splits after the breeding season, the partners remember each other and sometimes demonstrate, elements of breeding behavior in August or even September.

Denning. Dens are isolated from urban areas. The typical form are ground dens (85%) made under tree roots on dry slopes of north or north-east aspeqt. Ground dens are all of the same type: the size of the entrance (chelo) is limited by the thick roots of trees, after the entrance follows a funnel sometimes up to 120 cm long, entering into a chamber. Sometimes a new chamber can be dug up from inside, with or without new hole. Dens occupied by females have bedding, those with males have not. Bears prepare their dens in advance, from September-October, about 30 days before beginning of hibernation. If the old den is destroyed, a new one is made nearby. Sometimes there can be a few reserve dens even if the main one is in good state. When active, bears rest in temporary shelters without bedding but on a dry place (Revenko 1993).

Skull morphology. The skulls of the Kamchatka brown bear are uniform and all of the skulls are of the high-browed type; with enormous frontal sinuses that raise the forehead strongly above the level of the face. The following range of variation for adult skulls is exhibited by combining the measurements of 29 skulls in the U. S. National Museum and those published by Rowland Ward (1910, p. 512), Ognev (1931, pp. 149151), and Pocock (1932, pp. 796-797): Males, min. 390, max. 482; females, min. 319, max. 391 (Schwarz 1940). Cheek teeth are relatively small (length [R]4-[M]2 it is equal to on the average 20.4% of the condylobasal length (Baryshnikov, 2007).

(Skulls: Ognev S.I. 1931)

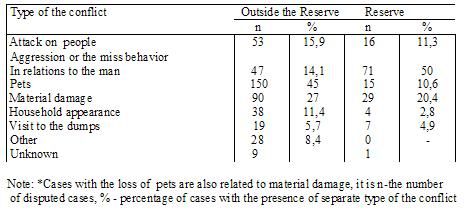

Relations with man. Because of the abundance of food resources, Kamchatka brown bears (similar to Kodiak brown bears) in general are not dangerous to humans, and only 1% of encounters result in attack (Revenko 1994). For conflict analysis between man and Kamchatka brown bear data from the administration of Rosselkhoznadzora (division of Okhotnadzora) for the period of 1973-2005 (official documents - 315 cases, from the newspaper reports - 17 cases and forms of participants in the conflicts - 10 cases) and the Chronicles of Nature of Kronotskogo state preserve in 1971-2004 time frame (129 cases) are recorded. In total, a review of the entered materials show 471 recorded conflicts. Analysis of the conflict situations were related to the cases of the aggressive behavior of bears with respect to humans, attacks on man and domestic animals, material damage to animals and livestock, appearance of brown bears in the places of human economic activity areas, and also the cases, which potentially could cause enumerated consequences ([podranki], connecting rods and others.

Territorial distribution of conflict, [Rosselkhoznadzor] conflict information which occurred in essence in the territories that do not have status of protection zones (hunting economies, the populated areas). As far as the regions they were distributed as follows: [Elizovskiy] - 154, Ust'- Kamchatka - 44, [Sobolevskiy] - 43, [Bolsheretskiy] - 17, [Milkovskiy] - 16, [Tigilskiy] - 15, [Bystrinskiy] - 12, [Penzhinskiy] - 11, [Karaginskiy] - 8, Ust' -[Bolsheretskiy] - 7, [Olyutorskiy] - 5, and in 10 cases region was not indicated. Conflicts in the preserve from the [Elizovskogo] region are 129 cases (Pachkovskiy et al. 2006).

Source: Pachkovskiy et al. 2006

Trophy Hunting. In the 1950-1960s there was no control over the bear hunting in Kamchatka. According to Ostroumov (1968) and Dunishenko (1976) the bear number s were reduced two fold compared to the counted data of the early 1960s. Introducing licenses in the mid-1970s was aimed at establishing a regulated harvest. Initially, a positive effect on the population but then hunters started to use the same license for shooting several bears. The demand for bear hunting in Kamchatka exceeded the number of issued licenses by a factor of seven and incidents of license bribery were also common.

Today, Russia's local and federal governments do not have enough money and managers to control this situation. There are only 3 researchers studying brown bears at this time. Researchers are understaffed, under-equipped, and lack adequate transportation resources. Money is offered to hunting companies to improve the economy, but nothing is contributed for research or for conservation. Attracting foreign hunters has become one way to improving the financial status of the game industry and also a potential source of funds for the protection of animals and research projects. In the mid 1990's, one bear license cost $6,000-7,000 USD. In this same period, Eco-tourism in Kamchatka has also showed conservation benefits and financial promise. Despite the promising improvement, conservation problems remain. While hunting companies are developing brown bear hunts for foreigners, the bear population are being hunted without adequate care to sufficient number management, gender control, and proper age guidelines which are not determined by bear specialists. Coupled with the problem of the illegal poaching trade, conservation and management worries for the future of the Kamchatka brown bear continue as such a cherished icon of the Far East could very well become a threatened species (Revenko 1994).

Management and Conservation. In 2002, the Society of the Retention of Wild Animals (Kamchatka) under the umbrella of the Pacific Ocean Institute of Geography continued the program for the study and management of brown bears. This project dates back to 1995. Until 2001, field studies were conducted, in essence, around the territory of southern Kurile Reservation, coordinated their by V. Likok (WCS). For the field season 2002, field works are produced in three model sections which have different ecological and geographical characteristics. Two sections were arranged on the east coast including on the east coast peninsula Kronotskiy State Biosphere Reserve ([Elizovskiy] region). The third place was selected on the west coast ([Sobolevskiy] region). Studies included the capture of bears, their immobilization and radio-labeling; radio tracking of marked animals; increased visual observations of the extraction of food-sources, behavior of bears monitoring; the improvement of methods in the calculation for the number of animals; the collection of hair samples for genetic analysis; greater study on morphology. The inspection of territories to determine the level of fitness for further studies (Seryodkin, Pachkovskiy 2004).

Conservation Recommendations. Zoologists advance the following conservation goals: 1) Sustainable funding in the amount of 20,000 to 25,000 USD per year in the implementation of conservation measures and monitoring; 2) Improved data on the illegal harvest of brown bears; 3) Efficient protection of key habitats within hunting grounds - in addition to existing protected territories (Valentsev A. S., Voropanov V. U., Gordienko V. N. 2005).

References

Baryshnikov, G.F. 2007. Fauna of Russia and Adjacent Countries (MAMMALS Volume I, issue 5) Ursidae (in Russian); Cherniavskii, F.B. Krechmar, M.A. 2001. Brown Bear in the Northeastern Siberia (in Russian); Dunishenko, Y.M. 1987. Distribution and numbers of the brown bear in Siberia and far east The Ecology of Bears (in Russian); Gordienko, V.N., Gordienko T.A. 2005. Brown Bear Kamchatka (short practical handbook on ecology and the prevention of conflicts, (in Russian); Koshcheev V. M. Ostanin Man and large predators: Administrative strategy. Kamchatka brown bear. Hunting and hunting. 1986. 5. 16 17. 136 (in Russian); Koshcheev V.M. On the influence of a brown bear on mortality of sea otters in the rookeries in the south of Kamchatka Nromyslovaya fauna of northern Natsifiki: Proceedings of the VNIIOZ them. prof. BM Zhitkova. Kirov, 1989. 78 84 (in Russian); Kurten Bjorn, 1973. Trans Berigian Relationships of Ursus arctos Linne (Brown and Grizzly Bear); Lobkov, E.G. 2006. Trophic Interaction between brown bear and birds on salmon spawning grounds in Kamchatka (in Russian); Los Angeles Times, July24, 2008. Starving Kamchatka brown bears eat two men, leave Russians in fear; Ognev, S. I. 1931. The mammals of eastern Europe and northern Asia, vol. 2, pp. 14-118; Ostroumov, A.G. 1968. Aerial visual census of brown bears. (Ursus arctos) in Kamchatka and some observations on their behavior Bull. Soc. Nat. Moscow LXXII (2) (In Russian); Pachkovskiy, D. H., Seryodkin I. V., Voropanov V. 2006. The conflict situations between the man and the brown bear in Kamchatka// the retention of [bioraznoobraziya] of Kamchatka and adjacent seas: Proceedings of the 7th International Scientific. Conference., dedicated to the 25th Anniversary Organization of Kamchatka. The division of the Institute of Pacific Biology - Petropavlovsk-Kamchatka: Kamchatka press, pp. 240-243 (in Russian); Pocock, R. I. 1932. The black and brown bears of Europe and Asia. Part I. Journal Bombay Natural History; Rausch L. Robert 1963. Geographic variation in size in North American brown bears, Ursus arctos L., as indicated by condylobasal length. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 41. 33-45; Revenko I.A., 1993. Kamchatka The Brown Bear in the Southern Far East, in Medvedi, Moscow, (in Russian); Revenko, I. A. 1994. Brown Bear (Ursus arctos piscator) Reaction to Humans on Kamchatka, Kamchatka Ecology and Environmental Institute, pr. Rybakov, 19 a, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy, 683024, (in Russian); Seryodkin I. V., Pachkovskiy D., Shevchenko I. N., 2004. Program of the retention of brown bear in Kamchatka// geographical and geo-ecological studies before the Far East, Vladivostok: Dalnauka. - pp. 53-56 (in Russian); Schwarz Ernest, 1940. Status and Affinities of the Bears of Northeastern Asia Journal of Mammalogy American Society of Mammalogists; Talbot SL, & Shields GF 1996. A phylogeny of the bears (Ursidae) inferred from complete sequences of three mitochondrial genes. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol.; 5:567-575; Valentsev A. S., Voropanov V. U., Gordienko V. N., 2005. Brown Bear management on Kamchatka; Vereshchagin N.K. 1971, Bears, Animal Life, v. 6. (in Russian); Vereshchagin N.K. 1973. Craniological characteristic of recent and fossil bears // Zoologicheskii Zhurnal. T.52. No.6. (in Russian); Vereshchagin N. K., 1976. The brown bear in Eurasia, particularity the Soviet Union // Bears — their biology and management / Eds M. R. Pelton, J. W. Lentfer, G. E. Folk. Morges. P. 327—335. (Inter. Union Conserv. Nature Publ., new ser. Vol. 40).

Administrative Note:

General bear profile threads will be locked and pinned, but follow up discussion thread(s) are available.

General Kamchatka brown bear profile (discussion):

shaggygod.proboards.com/index.cgi?action=display&board=piscator&thread=315

Bear photo & videos are located in the PHOTO GALLERY & VIDEO section.

Kamchatka Brown Bear Photo Thread:

shaggygod.proboards.com/index.cgi?board=eurasia&action=display&thread=35