|

|

Post by grrraaahhh on Apr 6, 2013 7:12:17 GMT -9

"On the basis of circumstantial evidence and an observed attack by 2 subadult brown bears that drew blood from a lone adult bison (Bison bison), brown bears are suspected to occasionally kill young bison, although none has been confirmed (M. Meagher 1973 and pers. commun.). Observations have also been made of individual brown bears testing lone bison by approaching them and then leaving when the bison ignored them, refused to run, and kept on feeding (M. Meagher pers. commun.). Healthy adult male bison may be too large and well armed for a bear to attack without risk of serious injury to itself. Testing likely helps a bear to identify a sick or weak animal. Bison also have a clumped distribution, especially during critical periods such as calving (Calef and Van Camp 1987), which may also make predation by bears difficult. In a review of historical material, Roe (1970) found evidence of brown bears scavenging on dead bison but it appears that predation was uncommon."Stirling, I. and AE Derocher. 1990. Factors affecting the evolution and behavioral ecology of the modern bears. International Conference on Bear Research and Management 8:189–204. PDF LINK: www.bearbiology.com/fileadmin/tpl/Downloads/URSUS/Vol_8/Stirling_Derocher_8.pdf

|

|

|

|

Post by grrraaahhh on Apr 8, 2013 15:00:04 GMT -9

A remarkable encounter and equally an impressive recounting of the event (remarkable detail):I drove east along the road, observing the movement of the bears and bison approximately 15 meters away. After trotting about 50 m, the bison broke into a full run. The adult bear then chased the bison at full speed. At the crest of the hill above the Yellowstone River, the bear swiped its paw across the hindquarters of the bison, knocking the bison's back legs out from under it. The bison began to slide down the steep embankment of the hill on its back. After striking a tree with considerable force on its front quarters, the inverted bison continued to slide toward a pedestrian boardwalk at the base of the hill. The grizzly leaped onto the stomach of the inverted bison and skidded down the hill on top of it while attempting to bite at the bison's neck. The bear and bison came to a stop at the base of the hill on the pedestrian boardwalk. The bear continued to bite and pull at the bison's neck while the bison tried to get to its feet. The bison managed to stand and struggled to remain standing, but the bear continued to pull the bison back down to the ground. When the bison did stand, its hind legs buckled under its own weight. The bear took advantage of this and jumped onto the back of the bison, biting and clawing at its back, inflicting a number of bite and claw wounds around the bison's hump and lower back. With a quick head motion, the bull managed to free itself from the bear and stand up a second time. At this time, I observed that the bison's left front leg was broken. This injury may have occurred when the bison slammed into the tree while sliding down the steep hill. The bison continued attempts to stand and fought off the bear with its head and horns for several minutes. The bear stood up on its hind legs and swiped at the bull's head with its paws. The bison reacted by rearing up, which caused it to slide backward into a ditch adjacent to the Fishing Bridge boardwalk. Being in the ditch appeared to put the bison in a better position to fend off the bear with its head and horns. At this time the 2 cubs, which had been observing their mother from on top of the hill, came down and reunited with her near the bison. The bison continued to struggle to keep up-right and bled profusely from its back and hindquarters. The adult bear attacked the bison several more times, but the bison was able to use its head and horns to repel the attacks. The cubs did not participate in these attacks but remained nearby. On 5 occasions the bears left the area and were no longer visible to me, then came back and the adult attacked the bull again, but was unable to kill it. The interval between attacks increased from approximately 5 minutes to several hours between return visits. At approximately 1800 the bears left and did not return, enabling me to investigate the bison in the ditch. The bison was startled upon my approach and attempted to climb out of the ditch. It fell down and was unable to pull itself out of the mud. Due to the proximity of the bison to the main road and concerns for the safety of visitors and a construction crew working on the road bridge adjacent to the attack site, park management decided to dispatch the bison and move the carcass. After shooting the bison, the carcass was moved 0.9 km away to a location remote from public use areas. Managers hoped that the bear family group would follow the scent trail to where the carcass was disposed and scavenge the remains. The next morning (24 September), an adult female grizzly with 2 cubs returned to the area where the attack occurred. The 3 bears were identical in size and color to the bears that had encountered the bison the previous day, and I believe they were the same family group. The adult female grizzly paced, circled, and sniffed the ground as she searched the site where she had attacked the bison the day before. Several visitors saw the bears from the main road and approached them in an attempt to get pictures. As they approached, the adult bear bluff charged them and chased them back toward the road. Due to the danger that an adult female grizzly accompanied by 2 cubs posed to park visitors and bridge construction workers, the bears were hazed out of the area with cracker shells. I monitored the area where the bison carcass was moved to, but never observed the female with cubs or their tracks in the snow at the new location. Three days later, I observed a large adult male grizzly scavenging on the carcass. I observed that bear at the carcass for 5 consecutive days and then did not see it again. In that time, the grizzly consumed most of the bison. After the grizzly stopped returning to the carcass, a large male black bear (Ursus americanus) began frequenting the carcass and scavenging the remains. The black bear returned to the carcass to scavenge for several days until the carcass was entirely consumed. I did not see the female and her 2 cubs in the area again for the remainder of the season. Tooth eruption and wear from the bison's mandible indicated it was 3 1/2 years old (M. Meagher, YNP, Wyoming, USA, personal communication, 2001). Femur bone marrow was grayish-pink in color, indicating that the bull may have been in the early stages of marrow fat depletion, although not yet severely malnourished (Cheatum 1949). Visually, the bison had looked slightly thin, but there was no other evidence of poor health or injury prior to the attack or when I observed it fleeing from the bear. Wyman, Travis. 2002. Grizzly bear predation on a bull bison in Yellowstone National Park. Ursus 13:375-376 PDF LINK (see first post) or the following hyperlink: www.bearbiology.com/fileadmin/tpl/Downloads/URSUS/Vol_13/Wyman_13.pdf  PDF/PHOTO LINK: www.greateryellowstonescience.org/files/pdf/YS_Wyman.pdf |

|

|

|

Post by sarus on Aug 21, 2013 3:16:05 GMT -9

|

|

|

|

Post by warsaw on Jan 16, 2014 15:39:54 GMT -9

|

|

|

|

Post by warsaw on Feb 12, 2014 10:05:10 GMT -9

"...Later in the week, we were alerted to a bison carcass by Caroline, an interpretive ranger. With much yelling and eyeing of the forest edges, we flushed the 30+ ravens off the carcass as we approached. The necropsy found significant subcutaneous hemorrhaging on the hump of the very healthy (lots of fat in the hump and marrow) cow bison, indicating that she was killed by a bear. Grizzly bears often attack from the front, as opposed to wolves, which typically attack from the rear. The bears basically give their prey a good swat in the face or jump them from the side and latch onto their back..." www.aspiringecologist.com/2010_03_01_archive.html |

|

|

|

Post by sarus on Aug 20, 2014 8:08:07 GMT -9

|

|

|

|

Post by warsaw on Feb 17, 2015 8:11:36 GMT -9

|

|

|

|

Post by warsaw on Mar 29, 2015 8:37:48 GMT -9

Yellowstone Bison: Conserving an American Icon in Modern Society Editors P.J. White, Rick L. Wallen, and David E. Hallac Contributing Authors Katrina L. Auttelet, Douglas W. Blanton, Amanda M. Bramblett, Chris Geremia, Tim C. Reid, Jessica M. Richards, Tobin W. Roop, Dylan R. Schneider, Angela J. Stewart, John J. Treanor, and Jesse R. White Contributing Editor Jennifer A. Jerrett Yellowstone Association Yellowstone National Park, USA, 2015 "...Winter-kill can be a significant cause of mortality during winters with severe snow pack (Fuller et al. 2007b; Geremia et al. 2009). Also, predation is becoming a larger factor following wolf restoration and grizzly bear recovery (Smith et al. 2004, 2013; Becker et al. 2009a,b). During 1993 through 2010, biologists from Montana State University found 656 bison carcasses in central Yellowstone during winter and spring and the apparent causes of death were 225 wolf predations, 181 winter-kills, 153 due to unknown causes, 46 grizzly bear predations, 20 thermal/mud entrapments, 10 vehicle strikes, 7 accidents/ injuries, 7 birth/pregnancy complications, 6 due to unknown predators, and 1 coyote predation (R. A. Garrott, Montana State University, unpublished data). .." www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/upload/Yellowstone_Bison_Final_ForWeb.pdf |

|

|

|

Post by sarus on Jan 30, 2020 19:24:47 GMT -9

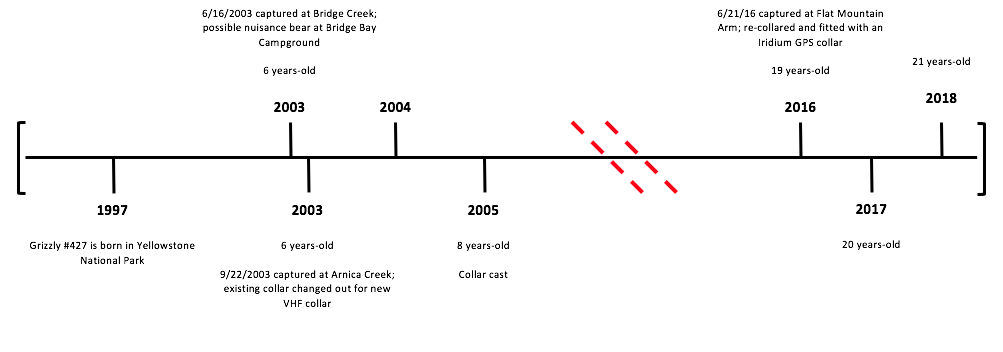

Preacher the Bison Killer in Action! Preacher preparing his sermon... (there is a river between him and the bison in this shot)   A last, desperate self-baptism by the Preacher bear ==================================================== ==================================================== For more photos and the whole story, visit the following blog:www.aspiringecologist.comwww.aspiringecologist.com/2010/04/very-beary.html==================================================== ==================================================== 6/11/2018  Grizzly #427: Not many people are familiar with grizzly #427 in Yellowstone National Park. #427 calls south and central Yellowstone his home. Frequently throughout his life, he has been observed on various spawning streams surrounding Yellowstone Lake. He has been dubbed the infamous “Preacher Bear.” Few visitors have been given the opportunity to watch #427 in action as he fishes for Cutthroat Trout in Little Thumb Creek, or Arnica Creek. No matter the case, when #427 does emerge as a ‘ghost’ from the wilderness, he doesn’t disappoint. In past years, others have watched him furiously attempt to break through thick ice near Bluff Point, or even rip through an old overwintered carcass near Old Faithful.  Timeline showing the known life events of grizzly #427 in Yellowstone National Park. We really only have a little snapshot of #427 life, and that was by pure accident. He was suspected to be a possible nuisance bear in the Bridge Bay Campground area in Lake District, and was captured for management purposes on June 16, 2003 at 6 years-old. At the time he was captured, he was fitted with a radio collar, relocated, and later released. On September 22, 2003, he was captured at Arnica Creek, YNP. In 2005, #427 cast his collar. He would not be collared again until June 21, 2016, when he was captured at Flat Mountain Arm and fitted with a new radio collar. As of 2018, #427 is currently 21 years-old. Most bears in Yellowstone live to be 25-30 years old.

► www.yellowstonegrizzlyproject.org/home/have-you-heard-of-the-preacher-bear

|

|