Biologists spreading misinformation: hybridization with grizzlies not due to polar bears moving inland

Posted on August 3, 2013 | Comments Off

A paper published last week in the journal Science, written by a team of biologists and atmospheric scientists, expounds on a possible dire future for a range of Arctic animals. It’s called, “Ecological consequences of sea-ice decline” and surprisingly, polar bears are discussed only briefly.

However, with the inclusion of one short sentence, the paper manages to perpetuate misinformation on grizzly/polar bear hybridization that first appeared in a commentary essay three years ago in Nature (Kelly et al. 2010)1. The Post et al. 2013 missive contains this astonishing statement (repeated by a Canadian Press news report):

“Hybridization between polar bears and grizzly bears may be the result of increasing inland presence of polar bears as a result of a prolonged ice-free season.”

Lead author of the paper, Professor of Biology Eric Post, is quoted extensively in the press release issued by his employer (Penn State University, pdf here). In it, Post re-states the above sentence in simpler terms, removing any doubt of its intended interpretation:

“… polar and grizzly bears already have been observed to have hybridized because polar bears now are spending more time on land, where they have contact with grizzlies.”

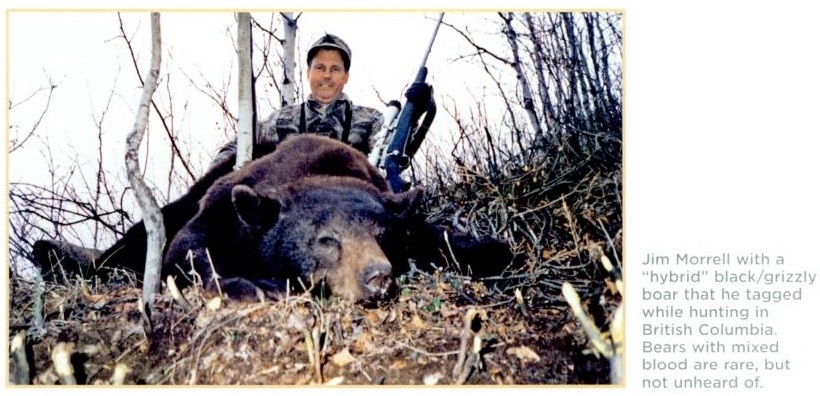

Both statements are patently false. All recent hybridization events documented (2006-2013) occurred because a few male grizzlies traveled over the sea ice into polar bear territory and found themselves a polar bear female to impregnate (see news items here and here, Fig. 1 below). These events did not occur on land during the ice-free season (which is late summer/early fall), but on the sea ice in spring (March-May).

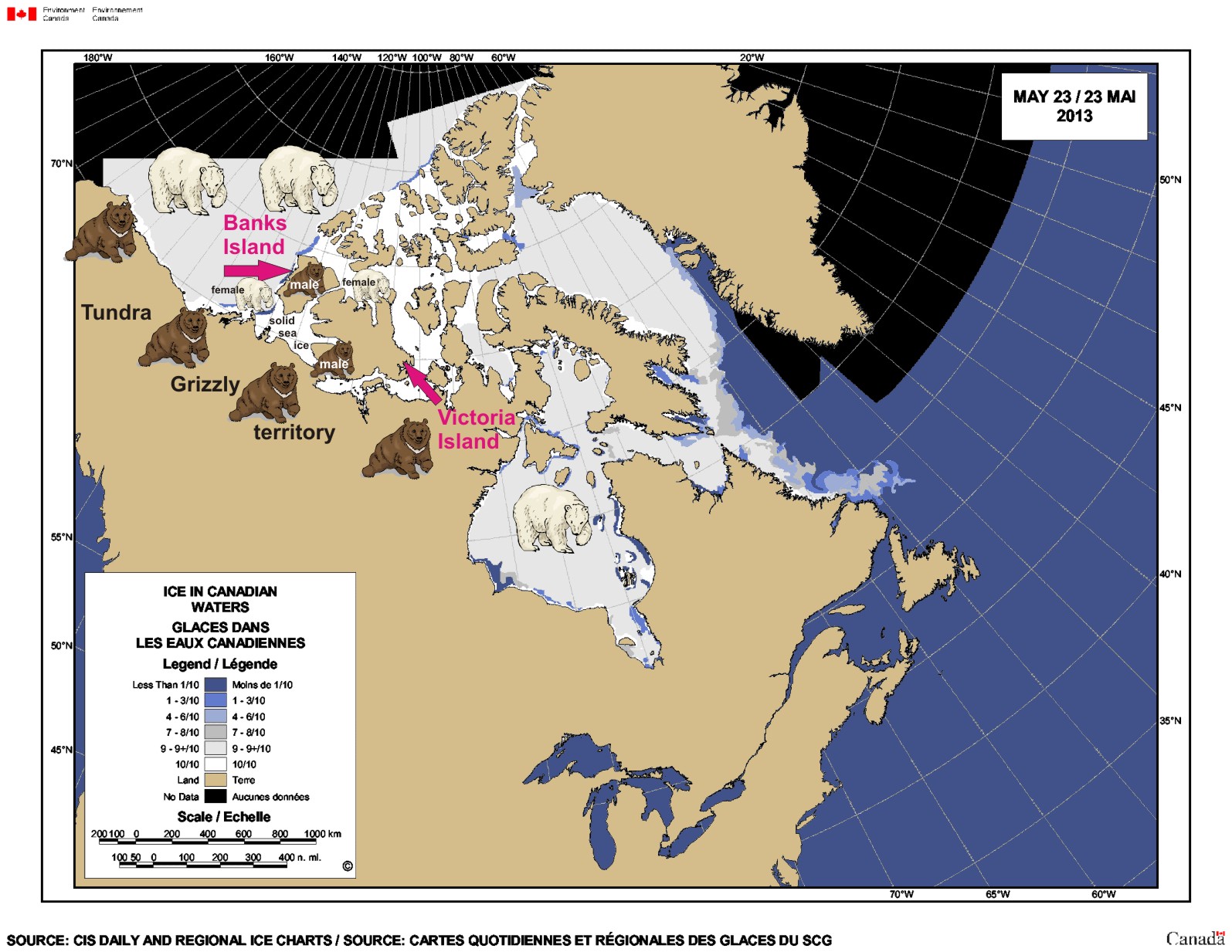

Grizzlies have been documented wandering over the sea ice of the western Arctic since at least 1885 (Doupe et al. 2007; Fig. 2, below) and the presence in this region of hybrid grizzly/polar bear offspring is not an indicator of declining summer sea ice, whether due to global warming or natural causes, or some combination thereof.

Leading polar bear specialist Ian Stirling knows this. He said as much in an interview with National Geographic News reporter John Roach when the first hybrid was shot back in 2006 (May 16, 2006), pdf here:

polarbearscience.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/stirling-hybrid-comment_nationalgeographic_com_news_pf_85960638_html_2006.pdfnews.nationalgeographic.com/news/2006/05/polar-bears.html“Stirling said grizzly bears have been showing up in the Canada’s western Arctic as far north as Banks Island and Victoria Island in the province of Nunavut (see these islands in the upper left of our Nunavut map) periodically for the past 50 years.

The hybrid, he said, is “definitely not” a sign of climate change.” [my bold]

Ian Stirling is not only a co-author on the Post et al. Science paper but he is the only polar bear specialist on the team. He may not have written this erroneous sentence; his less-experienced co-authors may have composed it. If so, he failed to correct it or insist it be removed. The responsibility for the inclusion of this blatant misrepresentation of fact in the Post et al. paper lies with Stirling, since he knows it’s not true.2

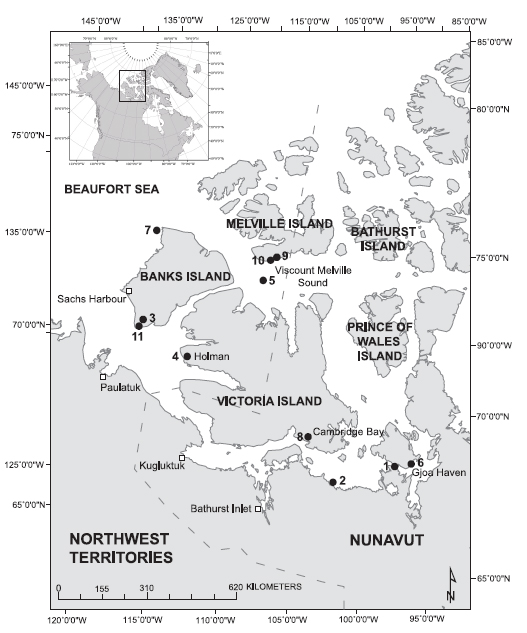

Figure 1. Sea ice extent in late spring in the western Arctic (May 23, 2013). Note that there is solid ice between the mainland and Banks and Victoria islands at this time. Some grizzly males emerge from their winter dens long before grizzly females and go wandering in search of food and potential mates: they can find both out on the sea ice beyond the coastline. See Fig. 2 for a history of grizzly excursions onto the sea ice and the Arctic islands, which have taken then even further north than Victoria Island. Click to enlarge.

Figure 1. Sea ice extent in late spring in the western Arctic (May 23, 2013). Note that there is solid ice between the mainland and Banks and Victoria islands at this time. Some grizzly males emerge from their winter dens long before grizzly females and go wandering in search of food and potential mates: they can find both out on the sea ice. See Fig. 2 for a history of grizzly excursions onto the sea ice and the western Arctic islands, which have taken then even further north than Victoria Island. Click to enlarge.

All recent hybridization events (2006-2013) have involved male grizzlies that moved north over the extensive ice present in spring, during the overlap in breeding time for the two species (see news items here and here; Fig 2, below). All polar bears are on the sea ice feeding at this time, unless they move onshore briefly to mate.

For example, a summary article published online by Alaska Science Forum writer Ned Rozell (April 2013) contains this interesting account:

“Dick Shideler, a biologist at the Alaska Department of Fish and Game in Fairbanks who studies the farthest-north grizzly, has documented grizzly bears on the sea ice north off Alaska’s coast.

“We’ve radio collared a grizzly bear who hunts seals in the spring,” Shideler said. “Our pilot has tracked him on the ice, going from hole to hole. He’s figured it out.”

Shideler also said biologists from the Northwest Territories have in the past shared reports of what could have been hybrid bears.

“There was a grizzly up there towards Banks Island that killed a bunch of seals, and (a pilot) tracked it and saw its tracks intersecting with those of a polar bear,” he said.”

Last year, I made a comment on this topic at Pierre Gosselin’s blog, which he elevated to a post (here). This is what I said:

“Both polar bears and grizzlies mate in the spring/early summer…Male tundra grizzlies are known to range over enormous distances and recently, have wandered over the spring sea ice, up onto the western Canadian Arctic islands. Therefore, recent hybridization events have occurred in polar bear territory, not grizzly territory.

In other words, modern grizzlies are going to the sea ice in the spring to mate with polar bears rather than polar bears going on land to mate with grizzlies.”

I also published formal comments in 2012 at the academic journals Science and Current Biology regarding hybridization in relation to polar bear evolution (see posts here and here), and published two recent posts on the topic earlier this year (here and here).

A peer-reviewed paper laying out all of the details regarding the recent hybridization events (including DNA results) was supposedly in the works last year by Northwest Territories government biologists, but so far, no such paper has been published.

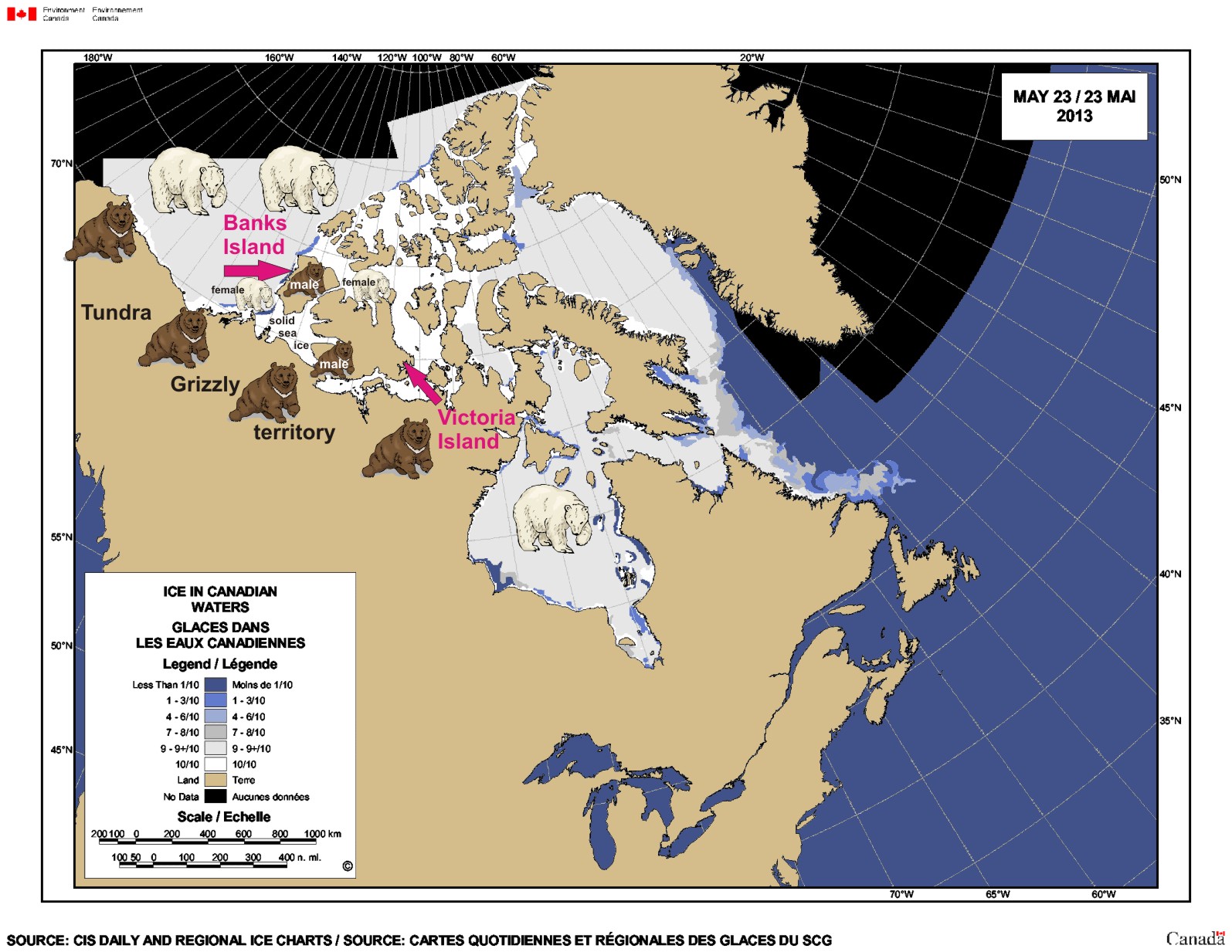

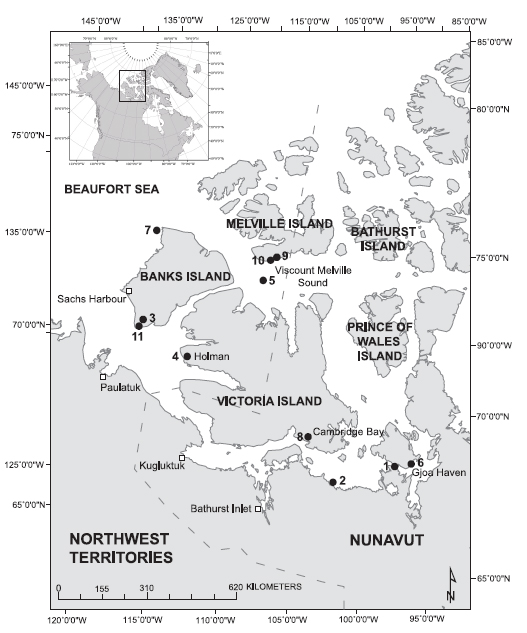

Figure 2. This map is Fig. 1 from the Doupé et al. (2007) paper. It shows the locations of “selected examples of grizzly bear sightings in the southern Canadian Arctic Archipelago," up to and including the hybrid shot in 2006. 1. Schwatka (1995 interprets the “unusual animals” sighted by Inuit in the Simpson Strait area as grizzly bears; 2) 1938: pair of grizzlies observed on the sea ice 24 m west of Perry River; 3)1951: hunter kills grizzly bear in Masik River valley, Banks Island; 4) 1986: one bear shot, another suspected in Holman; 5) 1991: bear tranquillized and examined on sea ice, 60 km south of Melville Island; 6) 1996-2002: five kill records in Gjoa Haven; 7) five-year-old male grizzly harvested around Gore Islands; 8) 2001:bear denned within 20 km of Cambridge Bay; 9) 2003: most northerly sighting of a grizzly bear in Canada, Cape Clarendon (this study); 10) 2004: tracks observed , DNA obtained, Cape Providence (this study); 11) 2006: grizzly-polar bear hybrid killed, Nelson Head. The paper is available free of charge (here).

Figure 2. This map is Fig. 1 from the Doupé et al. (2007) paper. It shows the locations of “selected examples of grizzly bear sightings in the southern Canadian Arctic Archipelago,” up to and including the hybrid shot in 2006. Original location notes:1. Schwatka (1885) interprets the “unusual animals” sighted by Inuit in the Simpson Strait area as grizzly bears; 2) 1938: pair of grizzlies observed on the sea ice 24 m west of Perry River; 3)1951: hunter kills grizzly bear in Masik River valley, Banks Island; 4) 1986: one bear shot, another suspected in Holman; 5) 1991: bear tranquillized and examined on sea ice, 60 km south of Melville Island; 6) 1996-2002: five kill records in Gjoa Haven; 7) five-year-old male grizzly harvested around Gore Islands; 8) 2001:bear denned within 20 km of Cambridge Bay; 9) 2003: most northerly sighting of a grizzly bear in Canada, Cape Clarendon (this study); 10) 2004: tracks observed , DNA obtained, Cape Providence (this study); 11) 2006: grizzly-polar bear hybrid killed, Nelson Head. The paper is available free of charge (here).

The bottom line is this: spring is when Arctic sea ice is at its maximum extent and the ice is thickest. All grizzlies have to do is walk across it from the mainland, which they have been known to do as far back as 1885.

Some polar bears in the western Arctic do come on land during the ice-free season in the late summer and at that time they can (and do) interact with tundra grizzlies – but the mating season is long over by then. Grizzlies and polar bears can mingle all they like while they’re together on land in the fall but a hybrid offspring is not going to result.

Ian Stirling knows this is true. He also knows that the statement made in Post et al. Science paper — and by Eric Post in the Penn State press release — misrepresents the facts. I can only conclude that Stirling either produced the statement himself for its propaganda value or allowed it to stand uncorrected for that purpose.

Footnote 1: The “authority” provided for the erroneous statement in the Post et al. paper is “Kelly et al. 2010.” The supplemental information associated with this paper (co-authored by seal specialist Brendan Kelly and two colleagues, none of whom are polar bear specialists), includes the following misleading statement (note that ‘supplemental information’ is a separate document published online only; it does not appear in the printed volume of the journal sent to public and university libraries):

“Polar bears may spend more time ashore rather than on sea ice, where they will increasingly encounter brown bears, some of which are expanding northward.”

Footnote 2: Brendan Kelly and colleagues are responsible for providing a statement not supported by fact in a peer-reviewed paper, which has encouraged the spread of this misinformation.

References

Doupé, J.P., England, J.H., Furze, M. and Paetkau, D. 2007. Most northerly observation of a grizzly bear (Ursus arctos) in Canada: photographic and DNA evidence from Melville Island, Northwest Territories. Arctic 60:271-276.

arctic.synergiesprairies.ca/arctic/index.php/arctic/article/view/219Kelly, B., Whiteley, A., and Tallmon, D. 2010. Comment: The Arctic melting pot. Nature 468:891.

www.nature.com/nature/journal/v468/n7326/full/468891a.htmlPost, E., Bhatt, U.S., Bitz, C.M., Brodie, J.F., Fulton, T.L., Hebblewhite, M., Kerby, J., Kutz, S.J., Stirling, I., Walker, D.A. 2013. Ecological consequences of sea-ice decline. Science 341:519-524. DOI: 10.1126/science.1235225

www.sciencemag.org/content/341/6145/519polarbearscience.com/2013/08/03/biologists-spreading-misinformation-hybridization-with-grizzlies-not-due-to-polar-bears-moving-inland/

arctic.synergiesprairies.ca/arctic/index.php/arctic/article/view/219