Post by grrraaahhh on Aug 19, 2011 2:24:09 GMT -9

Systematic Palaeontology

Class: Mammalia Linnaeus, 1758

Order: Carnivora Bowdich, 1821

Family: Ursidae Gray, 1825

Subfamily: Tremarctinae Merriam and Stock, 1925

Arctotherium Burmeister, 1879

Arctotherium angustidens Gervais and Ameghino, 1880

Geographic and stratigraphic distribution. Early to middle Pleistocene (Ensenadan) of the Pampean region of Argentina, Pleistocene of Bolivia (Soibelzon et al. 2005).

"The fossil record indicates that at the end of Ensenada, these giant bears disappear and also the ways in larger herbivores. We have initiated a research project focused on the study of ecosystems that point in time in order to approach this issue with more data and accuracy, "says Soibelzon

There are three associated SFB from Buenos Aires province, Argentina. These individuals are assigned to the En-senadan (early to middle Pleistocene) species Arctotherium angustidens Gervais & Ameghino, 1880, the giant South American SFB. Of the five Arctotherium species this is the only one recorded in the Ensenadan and it is the largest; among ursids only some individuals of Arctodus simus (Cope, 1879) approach its size (see Gobetz & Martin 2001 and Soibelzon 2002).

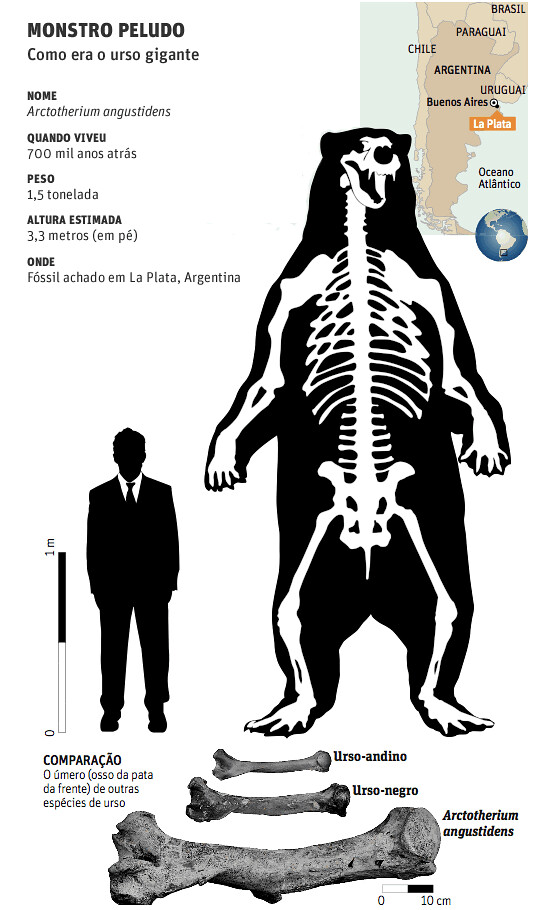

The remains were unearthed during the construction of a hospital in La Plata City, Argentina. It was a South American giant short-faced bear (Arctotherium angustidens), the earliest and largest member of its genus (its group of species of bears). This titan lived between 2 million to 500,000 years ago, with its closest living relative being the spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus) of South America.

“One of the things about collections is often times, especially in really big museums, is a lot of material gets collected and not everything gets studied,” Schubert said. “And so this specimen just sat in the museum.”

Schubert adds, “It was a species that we knew was really large... we just didn’t know quite how large it could get."

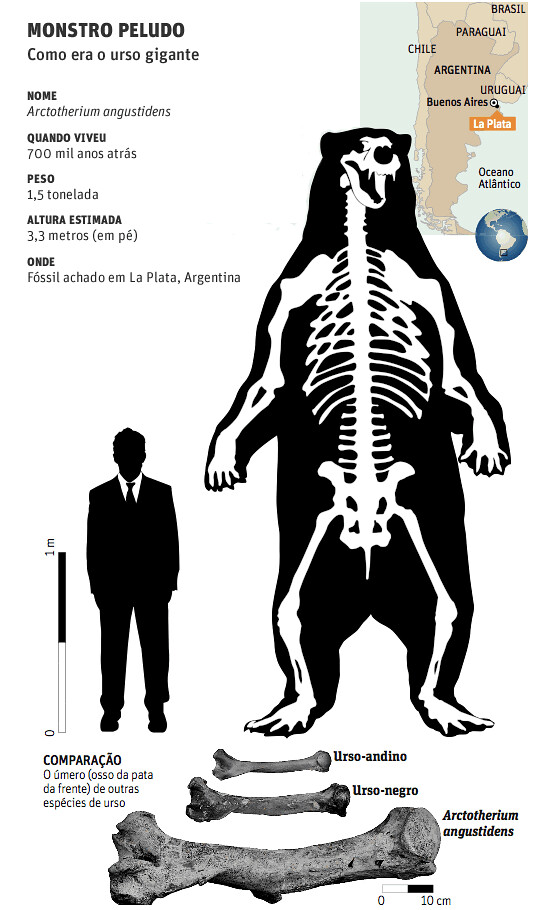

Size & Weight. Based on measurements of the fossil's leg bones and equations used to estimate body mass, the researchers say the bear would have stood at least 11 feet tall (3.3 meters) on its hind legs and would have weighed between 3,500 and 3,855 pounds (1,588 and 1,749 kilograms). In comparison, "the largest record for a living bear is a male polar bear that obtained the weight of about 2,200 pounds (1,000 kg)," said researcher Leopoldo Soibelzon, a paleontologist at the La Plata Museum.

"During its time, this bear was the largest and most powerful land predator in the world," researcher Blaine Schubert, a paleontologist at East Tennessee State University in Johnson City, told LiveScience. "It's always extremely exciting to find something that's the largest of its class — and not just a little bit larger, but quite a bit larger."

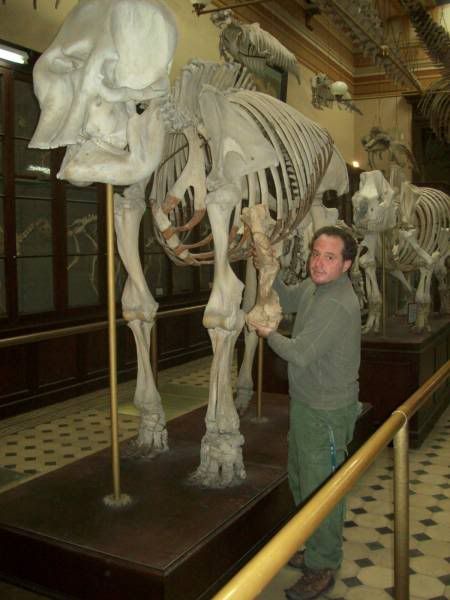

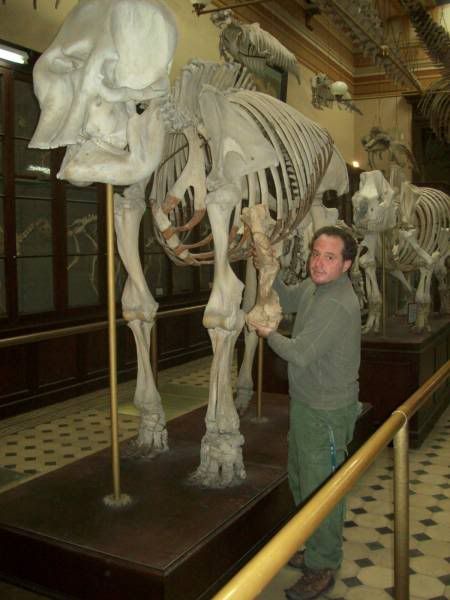

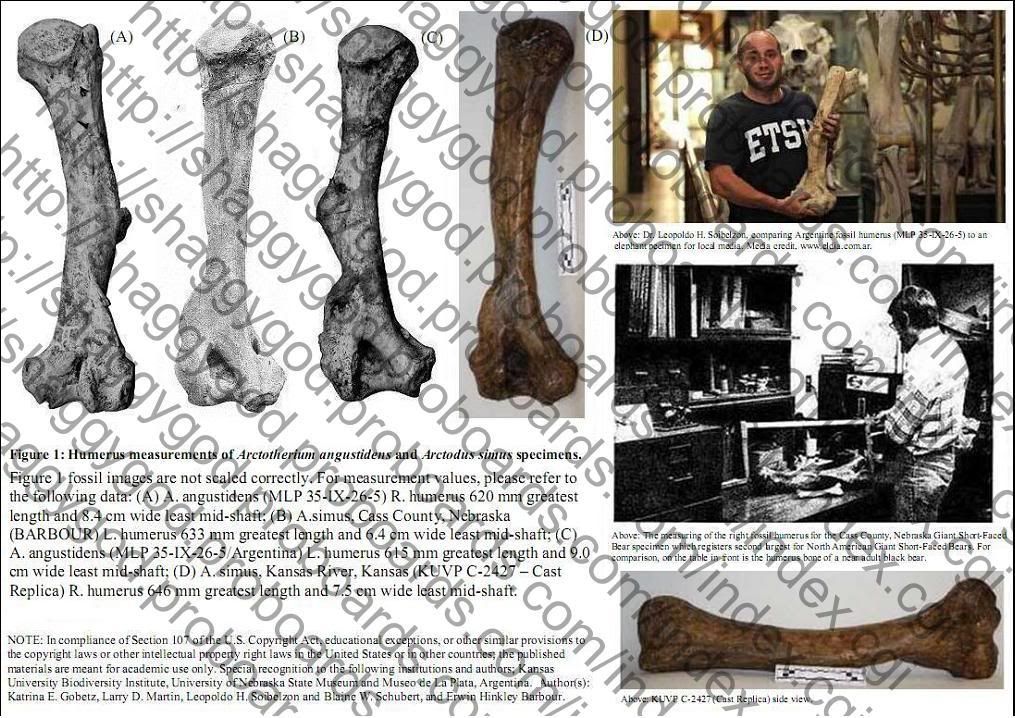

Above: Dr. Leopoldo, H.Soibelzon making a humerus comparison between Arctotherium angustidens and an elephant humerus.

Diet. Although this bear probably had an omnivorous diet, flesh likely dominated. Megafauna or large creatures likely played an important role in what it ate, and potentially included giant ground sloths, now-extinct relatives of elephants, camels, tapirs, and armadillo-like creatures known as glyptodonts.

No one really knows why animals were a certain size, including the giant bear in South America, but speculation ranges from having too much competition to not enough competition. What was occurring, though, in South America at the time was migrations of animals between North America and South America. This happened because land was forming for the first time between the continents.

Behaviors are not exactly known, either, but paleontologists like Schubert can make educated guesses.

“We think that these bears were omnivores, which means that they ate both plants and animals, but they probably ate a lot of meat,” Schubert said. “Based on their size they were probably dominating carcasses. They were probably scaring other animals off of carcasses, even if they weren’t doing a lot of their own hunting.”

"This does not imply that active hunting was its primary strategy for feeding, since its large size and great power may have permitted the bear to fight for prey hunted by other Pleistocene carnivores such as the saber-toothed cat," Schubert said. "Scavenging megaherbivore carcasses was probably another frequent way of feeding."

Sexual dimorphism. With the males being larger than females, occurs in all living bears and is more extreme in the larger species (Stirling, 1993; Stirling and Derocher, 1993). A number of authors have discussed sexual dimorphism in North American short-faced bears because two distinct sizes have been noted (e.g., Kurten, 1967; Kurten and Anderson, 1980; Churcher et al, 1993; Scott and Cox, 1993; Schubert and Kaufmann, 2003; Schubert et al, 2010; Schubert, 2010). While similar studies have not yet been done on Arctotherium angustidens, we infer that the individual described here was a male based on its exceedingly large size.

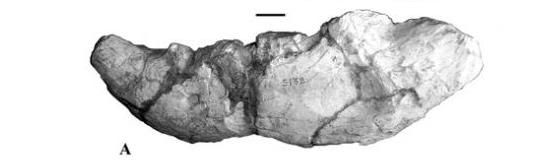

Left: Adult female mandible (A. angustidens). Right: Blaine W. Schubert holding a skull from the North American Giant Short-Faced bear skull.

The arm bones of the bear were used to by Schubert and Soibelzon to identify the creature. The upper arm bones had been broken and actually became infected, Schubert said. This could have been the result of hunting or fighting other bears or carnivores.

“So this would have been a very large bear that probably had a bad attitude,” Schubert said.

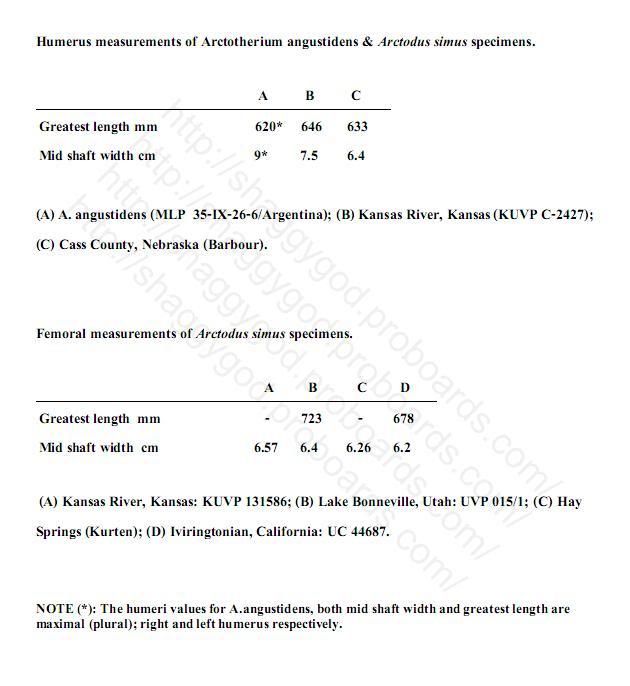

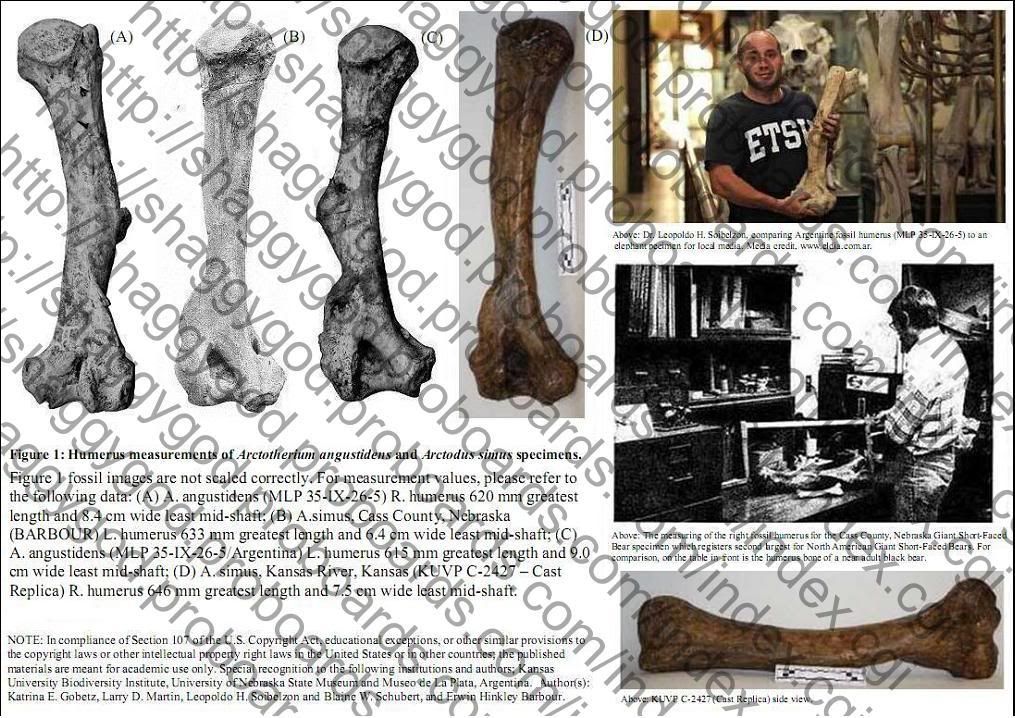

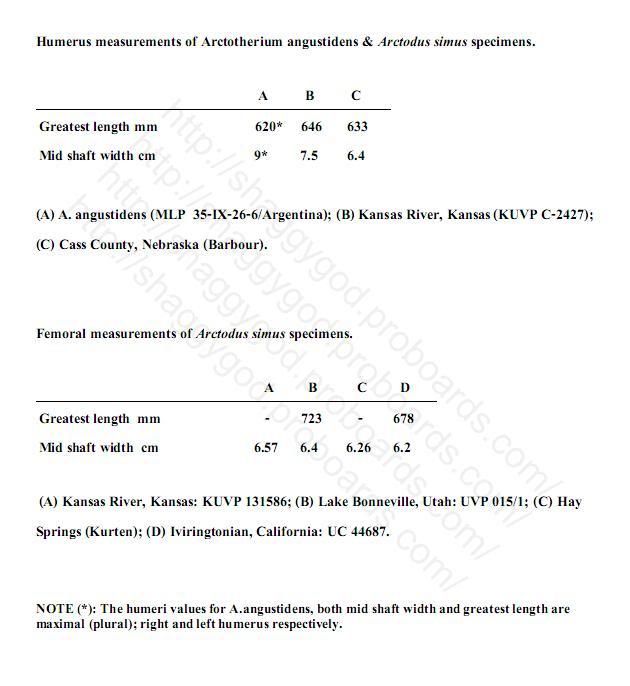

Above: As the data reveals, although there are North American A.simus specimens that produce longer humerus values, a review of the mid shaft width values tell us that A.angustidens is the heavier built bear. Comparable femoral data suggest a similar conclusion.

For more, read here: shaggygod.proboards.com/index.cgi?board=americaspleistocene&action=display&thread=454&page=1

Skull Morphology. Juvenile specimens, described here, provide information on the morphological changes of skull that occur during the transition from juvenile to adult. In this respect, it is evident that the skull is more vaulted in juveniles but wide and flat in adults. The nostril opening, the mastoid process, and the sagittal and lambdoid crests are all much larger and the palate wider in relation to the skull size in adults. The front is oblique and the nasals form a concave platform in juveniles; in adults the front is vertical and the nasals are very convex. The zygomatic arches are heavier and well separated from the skull in adults. In addition, the muscular insertion marks on the occipital region are stronger in adults.

In summary, A. angustidens is not very frequently recorded (similar to other members of Carnivora) but represents a conspicuous element of the M. cristatum biozone. Furthermore, A. angustidens is a characteristic species of the Ensenadan, and its biochron comprises the temporal lapse between 1.76 Ma (chron C1r2r) and 0.78 Ma (base of chron C1n) (Soibelzon et al., 2001).

References

Churcher, C.S., Morgan, A.V., and Carter, L.D. 1993. Arctodus simus from the Alaskan Arctic Slope. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 30: 1007–1013.

FIGUEIRIDO, B. SOIBELZON, L. H., 2009. Inferring palaeoecology in extinct tremarctine bears (Carnivora, Ursidae) using geometric morphometrics Lethaia:VOL 43; NUMBER 2, pages 209-222.

Kurten, B. (1967): Pleistocene bears of North America: 2. genus Arctodus, short-faced bears. Acta Zoologica Fennica 117:1-60.

Kurten. B., & Anderson, E. (1980). Pleistocene Mammals of North America. New York: Columbia University Press.

López, A. García-Daniel, Ortiz, E. Pablo, Madozzo Jaén, M. Carolina, and Moyano, M. Sebastián. 2008. First Record of Arctotherium (Ursidae, Tremarctinae) in Northwestern Argentina and its Paleobiogeographic Significance, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28(4):1232-1237.

SCHUBERT, B. W. AND J. E. KAUFMANN. 2003. A partial short-faced bear skeleton from an Ozark cave with comments on the paleobiology of the species. Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, 65:101–110.

Schubert, B. W., R. C. Hulbert, Jr., B. J. MacFadden, M. Searle, and S. Searle. 2010. Giant short-faced bears (Arctodus simus) in Pleistocene Florida USA, a substantial range extension. Journal of Paleontology 84(1):79-87.

Schubert, Blaine. JohnsonCityPress Interview, Friday, February 18, 2011.

Soibelzon, H. Leopoldo H, Eduardo P. Tonni and Mariano Bond The fossil record of South American short-faced bears (Ursidae, Tremarctinae)Journal of South American Earth Sciences Volume 20, Issues 1-2, October 2005, Pages 105-113 Quaternary Paleontology and biostratigraphy of southern South Africa.

Soibelzon, L.; Pomi, L.; Tonni, E.; Rodriguez, S.; Dondas, A.First report of a South American short-faced bears' den (Arctotherium angustidens): Palaeobiological and palaeoecological implications 2009, Alcheringa 33: 211-222.

Soibelzon, H. Leopoldo and Blaine W. Schubert2, The Largest Known Bear, Arctotherium angustidens, from the Early Pleistocene Pampean Region of Argentina: With a Discussion of Size and Diet Trends in Bears. Journal of Paleontology; January 2011; v. 85; no. 1; p. 69-75.

Stirling, I. 1993. The living bears. p. 36–49. In Sterling, I. (ed.). Bears: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. Rodale Press.

Class: Mammalia Linnaeus, 1758

Order: Carnivora Bowdich, 1821

Family: Ursidae Gray, 1825

Subfamily: Tremarctinae Merriam and Stock, 1925

Arctotherium Burmeister, 1879

Arctotherium angustidens Gervais and Ameghino, 1880

Geographic and stratigraphic distribution. Early to middle Pleistocene (Ensenadan) of the Pampean region of Argentina, Pleistocene of Bolivia (Soibelzon et al. 2005).

"The fossil record indicates that at the end of Ensenada, these giant bears disappear and also the ways in larger herbivores. We have initiated a research project focused on the study of ecosystems that point in time in order to approach this issue with more data and accuracy, "says Soibelzon

There are three associated SFB from Buenos Aires province, Argentina. These individuals are assigned to the En-senadan (early to middle Pleistocene) species Arctotherium angustidens Gervais & Ameghino, 1880, the giant South American SFB. Of the five Arctotherium species this is the only one recorded in the Ensenadan and it is the largest; among ursids only some individuals of Arctodus simus (Cope, 1879) approach its size (see Gobetz & Martin 2001 and Soibelzon 2002).

The remains were unearthed during the construction of a hospital in La Plata City, Argentina. It was a South American giant short-faced bear (Arctotherium angustidens), the earliest and largest member of its genus (its group of species of bears). This titan lived between 2 million to 500,000 years ago, with its closest living relative being the spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus) of South America.

“One of the things about collections is often times, especially in really big museums, is a lot of material gets collected and not everything gets studied,” Schubert said. “And so this specimen just sat in the museum.”

Schubert adds, “It was a species that we knew was really large... we just didn’t know quite how large it could get."

Size & Weight. Based on measurements of the fossil's leg bones and equations used to estimate body mass, the researchers say the bear would have stood at least 11 feet tall (3.3 meters) on its hind legs and would have weighed between 3,500 and 3,855 pounds (1,588 and 1,749 kilograms). In comparison, "the largest record for a living bear is a male polar bear that obtained the weight of about 2,200 pounds (1,000 kg)," said researcher Leopoldo Soibelzon, a paleontologist at the La Plata Museum.

"During its time, this bear was the largest and most powerful land predator in the world," researcher Blaine Schubert, a paleontologist at East Tennessee State University in Johnson City, told LiveScience. "It's always extremely exciting to find something that's the largest of its class — and not just a little bit larger, but quite a bit larger."

Above: Dr. Leopoldo, H.Soibelzon making a humerus comparison between Arctotherium angustidens and an elephant humerus.

Diet. Although this bear probably had an omnivorous diet, flesh likely dominated. Megafauna or large creatures likely played an important role in what it ate, and potentially included giant ground sloths, now-extinct relatives of elephants, camels, tapirs, and armadillo-like creatures known as glyptodonts.

No one really knows why animals were a certain size, including the giant bear in South America, but speculation ranges from having too much competition to not enough competition. What was occurring, though, in South America at the time was migrations of animals between North America and South America. This happened because land was forming for the first time between the continents.

Behaviors are not exactly known, either, but paleontologists like Schubert can make educated guesses.

“We think that these bears were omnivores, which means that they ate both plants and animals, but they probably ate a lot of meat,” Schubert said. “Based on their size they were probably dominating carcasses. They were probably scaring other animals off of carcasses, even if they weren’t doing a lot of their own hunting.”

"This does not imply that active hunting was its primary strategy for feeding, since its large size and great power may have permitted the bear to fight for prey hunted by other Pleistocene carnivores such as the saber-toothed cat," Schubert said. "Scavenging megaherbivore carcasses was probably another frequent way of feeding."

Sexual dimorphism. With the males being larger than females, occurs in all living bears and is more extreme in the larger species (Stirling, 1993; Stirling and Derocher, 1993). A number of authors have discussed sexual dimorphism in North American short-faced bears because two distinct sizes have been noted (e.g., Kurten, 1967; Kurten and Anderson, 1980; Churcher et al, 1993; Scott and Cox, 1993; Schubert and Kaufmann, 2003; Schubert et al, 2010; Schubert, 2010). While similar studies have not yet been done on Arctotherium angustidens, we infer that the individual described here was a male based on its exceedingly large size.

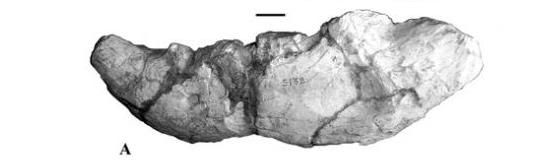

Left: Adult female mandible (A. angustidens). Right: Blaine W. Schubert holding a skull from the North American Giant Short-Faced bear skull.

The arm bones of the bear were used to by Schubert and Soibelzon to identify the creature. The upper arm bones had been broken and actually became infected, Schubert said. This could have been the result of hunting or fighting other bears or carnivores.

“So this would have been a very large bear that probably had a bad attitude,” Schubert said.

Above: As the data reveals, although there are North American A.simus specimens that produce longer humerus values, a review of the mid shaft width values tell us that A.angustidens is the heavier built bear. Comparable femoral data suggest a similar conclusion.

For more, read here: shaggygod.proboards.com/index.cgi?board=americaspleistocene&action=display&thread=454&page=1

Skull Morphology. Juvenile specimens, described here, provide information on the morphological changes of skull that occur during the transition from juvenile to adult. In this respect, it is evident that the skull is more vaulted in juveniles but wide and flat in adults. The nostril opening, the mastoid process, and the sagittal and lambdoid crests are all much larger and the palate wider in relation to the skull size in adults. The front is oblique and the nasals form a concave platform in juveniles; in adults the front is vertical and the nasals are very convex. The zygomatic arches are heavier and well separated from the skull in adults. In addition, the muscular insertion marks on the occipital region are stronger in adults.

In summary, A. angustidens is not very frequently recorded (similar to other members of Carnivora) but represents a conspicuous element of the M. cristatum biozone. Furthermore, A. angustidens is a characteristic species of the Ensenadan, and its biochron comprises the temporal lapse between 1.76 Ma (chron C1r2r) and 0.78 Ma (base of chron C1n) (Soibelzon et al., 2001).

References

Churcher, C.S., Morgan, A.V., and Carter, L.D. 1993. Arctodus simus from the Alaskan Arctic Slope. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 30: 1007–1013.

FIGUEIRIDO, B. SOIBELZON, L. H., 2009. Inferring palaeoecology in extinct tremarctine bears (Carnivora, Ursidae) using geometric morphometrics Lethaia:VOL 43; NUMBER 2, pages 209-222.

Kurten, B. (1967): Pleistocene bears of North America: 2. genus Arctodus, short-faced bears. Acta Zoologica Fennica 117:1-60.

Kurten. B., & Anderson, E. (1980). Pleistocene Mammals of North America. New York: Columbia University Press.

López, A. García-Daniel, Ortiz, E. Pablo, Madozzo Jaén, M. Carolina, and Moyano, M. Sebastián. 2008. First Record of Arctotherium (Ursidae, Tremarctinae) in Northwestern Argentina and its Paleobiogeographic Significance, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28(4):1232-1237.

SCHUBERT, B. W. AND J. E. KAUFMANN. 2003. A partial short-faced bear skeleton from an Ozark cave with comments on the paleobiology of the species. Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, 65:101–110.

Schubert, B. W., R. C. Hulbert, Jr., B. J. MacFadden, M. Searle, and S. Searle. 2010. Giant short-faced bears (Arctodus simus) in Pleistocene Florida USA, a substantial range extension. Journal of Paleontology 84(1):79-87.

Schubert, Blaine. JohnsonCityPress Interview, Friday, February 18, 2011.

Soibelzon, H. Leopoldo H, Eduardo P. Tonni and Mariano Bond The fossil record of South American short-faced bears (Ursidae, Tremarctinae)Journal of South American Earth Sciences Volume 20, Issues 1-2, October 2005, Pages 105-113 Quaternary Paleontology and biostratigraphy of southern South Africa.

Soibelzon, L.; Pomi, L.; Tonni, E.; Rodriguez, S.; Dondas, A.First report of a South American short-faced bears' den (Arctotherium angustidens): Palaeobiological and palaeoecological implications 2009, Alcheringa 33: 211-222.

Soibelzon, H. Leopoldo and Blaine W. Schubert2, The Largest Known Bear, Arctotherium angustidens, from the Early Pleistocene Pampean Region of Argentina: With a Discussion of Size and Diet Trends in Bears. Journal of Paleontology; January 2011; v. 85; no. 1; p. 69-75.

Stirling, I. 1993. The living bears. p. 36–49. In Sterling, I. (ed.). Bears: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. Rodale Press.