|

|

Post by grrraaahhh on Apr 19, 2011 6:41:03 GMT -9

|

|

|

|

Post by warsaw on May 15, 2011 11:17:43 GMT -9

|

|

|

|

Post by grrraaahhh on Aug 16, 2011 13:54:47 GMT -9

|

|

|

|

Post by grrraaahhh on Jan 25, 2012 10:22:56 GMT -9

From author Laura Cunningham. Some of you might be familiar Laura Cunningham's oil canvas paintings (they have been highlighted and promoted in this forum) depicting early California wildlife. However, I was not aware she had published a book which I am also happy to promote: From author Laura Cunningham. Some of you might be familiar Laura Cunningham's oil canvas paintings (they have been highlighted and promoted in this forum) depicting early California wildlife. However, I was not aware she had published a book which I am also happy to promote:Vernal pools, protected lagoons, grassy hills rich in bunchgrasses and, where the San Francisco Bay is today, ancient bison and mammoths roaming a vast grassland. Through the use of historical ecology, Laura Cunningham walks through these forgotten landscapes to uncover secrets about the past, explore what our future will hold, and experience the ever-changing landscape of California. Combining the skill of an accomplished artist with a passion for landscapes and training as a naturalist, Cunningham has spent over two decades pouring over historical accounts, paleontology findings, and archaeological data. Traveling with paintbox in hand, she tracked the remaining vestiges of semipristine landscape like a detective, seeking clues that revealed the California of past centuries. She traveled to other regions as well, to sketch grizzly bears, wolves, and other magnificent creatures that are gone from California landscapes. In her studio, Cunningham created paintings of vast landscapes and wildlife from the raw data she had collected, observations in the wild, and knowledge of ecological laws and processes. Through A State of Change, readers are given the pure pleasure of wandering through these wondrous and seemingly exotic scenes of Old California and understanding the possibilities for both change and conservation in our present-day landscape. A State of Change is as vital as it is visionary. Publication Month: October 2010 Hardcover, 978-1-59714-136-9, $50 352 pages (8.5 x 11) Nature/History www.a-state-of-change.com/Book.htmlSome of Laura Cunningham's oil canvas paintings: What did California look like before people? Grizzly bears at the shore. www.berkeleyside.com/2010/11/09/what-did-california-look-like-before-people/ Grizzlies gather to catch Chinooks moving over shallows on the Sacramento River. Oil on cotton rag paper, 7.5 x 10 inches, 2005.  Chinook run in the old San Joaquin River, before the Age of Dams. Oil on cotton rag paper, 8 x 20 inches, 2005.  Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) male in spawning colors. Oil on cotton rag paper, 13 x 30 inches, 1998. Please visit the following the link for more reading: www.a-state-of-change.com/Salmon.html |

|

|

|

Post by grrraaahhh on Jun 20, 2012 4:06:16 GMT -9

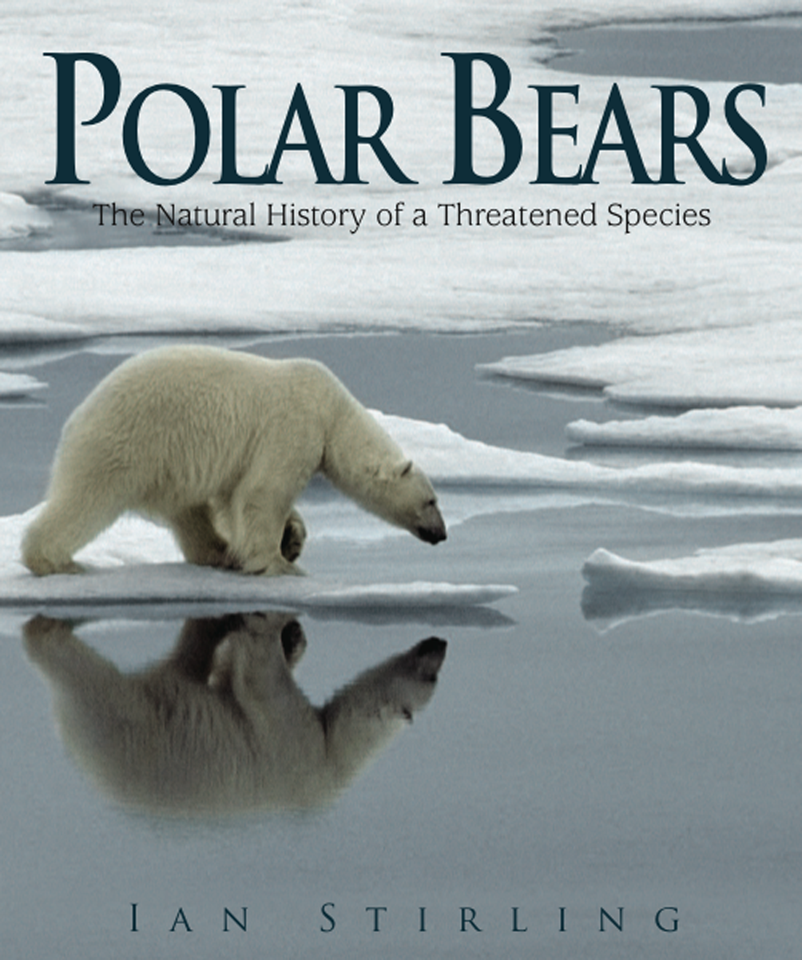

If you are a polar bear fan, you will want to own Dr. Ian Stirling's latest (2011) book. |

|

|

|

Post by warsaw on Aug 18, 2013 3:12:33 GMT -9

The Bear: History of a Fallen King

by Michel Pastoureau, George Holoch

www.freeebookse.com/The-Bear-History-of-a-Fallen-King-PDF2-244703/The Bear: History of a Fallen King (review) Irven M. Resnick From: The Catholic Historical Review Volume 98, Number 3, July 2012 pp. 528-529 | 10.1353/cat.2012.0188 In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content: Michel Pastoureau’s The Bear: History of a Fallen King is a fascinating cultural history, but one that seems to come up short. In part I, Pastoureau points to a lost communion between man and bear, such that “ancient peoples in the Paleolithic considered the bear a creature apart” (p. 25) and elevated the bear to become a totemic animal. Later, Greco-Roman, Celtic, and Germanic mythologies evidence a cult of the bear and provide enduring tales of metamorphoses of human into bear; of protective she-bears that nurse human infants; and of monstrous love, sometimes fertile, between a human female and a bear. Although the bear was venerated in early-medieval culture for its strength, its close resemblance to man and its allegedly insatiable sexual appetite prepared the foundation for a more violent confrontation with ecclesiastical authority. Since the theology of the Church depended on man’s uniqueness and superiority to animals, precisely because the bear so nearly resembled man, Pastoureau contends, churchmen sought to suppress rites or festivals that included the bear: Hincmar, archbishop of Reims, condemned “vile games with the bear” (p. 83); and other bishops, too, condemned festivals in which men dressed as bears or danced with them. Until the end of the Middle Ages churchmen repeated that men should not “play the bear” (p. 83), which entailed not only adopting a bear disguise but also manifesting uncontrollable sexual desire. Thus, the Church “went to war” (p. 89) against the bear, organizing hunts to nearly eliminate European bear populations. It attacked the bear’s legendary strength by depicting it in hagiographical literature as tamed and domesticated by holy men, and it demonized the bear as the embodiment of numerous vices and as the preferred form in which the devil appears. Finally, it humiliated the bear, allowing it to be captured, muzzled, chained, and led from fair to market as an object of amusement. Once the Church “dethroned” the bear as king of the beasts after 1000 AD, it replaced him with the lion—an exotic, distant animal whose symbology could be easily controlled. By the end of the twelfth century, the lion began to replace the bear on armorial bearings and in royal menageries. The bear’s diminished status is best illustrated for Pastoureau in vernacular literature: in the chansons de geste, or in French fabliaux like the Roman de Renart, in which the bear is reduced to a foolish, stupid, clumsy creature. Although Pastoureau’s study contains abundant fabulous material from medieval bestiaries and vernacular literature to fascinate the historian, this also underscores one of its shortcomings—it ignores challenges from natural philosophy following the introduction of Aristotle’s biology. Although many Scholastic texts do repeat the fantastic claim that bears couple like humans, face to face, they challenge other mythic characteristics. For example, the natural philosopher Albert the Great (d. 1280), in his commentary De animalibus, remarks that the bear is not very lustful (parum luxurians; DA 7.3.3.157). To the myth that the she-bear gives birth to an unformed cub and then brings it to life by licking it, Albert replies “none of this is true at all.” (DA 7.3.3.159) Although Alexander Neckam (d. 1217) does accept this myth, he does not attribute it, as Pastoreaux suggests was common, to the she-bear’s unsurpassing lust but rather to the bear’s humoral complexion, which causes the cotillidones that bind the fetus to the womb to rend, resulting in premature birth. (De naturis rerum, 2.131) Nevertheless, The Bear contains much that will inform and entertain. muse.jhu.edu/login?auth=0&type=summary&url=/journals/catholic_historical_review/v098/98.3.resnick.htmlThe History of a Fallen King By JONATHAN SUMPTION Relations between man and the animal world have a complex history, with attitudes shifting between intimacy, awe and exploitation. Animals have been objects of fear and worship. Over the centuries, they have provided humans with food, protection, companionship and entertainment. More recently, hygiene, convention and industrialization have combined to distance mankind from the natural world. Animals have become aliens, even when they live in our houses, provoking in turns the irrational disgust and anthropomorphic sentimentality that we reserve for beings that we do not care to understand. Enlarge Image Probst - ullstein bild / Granger Collection The coat of arms of Greenland. Michel Pastoureau is a highly original French cultural historian, a medievalist by training, who has made his reputation by writing about things that no one realized had a history. He has written the history of colors (black, blue, stripes). He has written the history of animals (pigs, now bears). Or, rather, he has written about man's attitudes toward these things. The common theme in his work has been mankind's habit of investing the nonhuman world with two layers of meaning, the one literal and the other symbolic. Mr. Pastoureau came to his subjects not, like most observers, through psychology but through the study of heraldry. Heraldry can be a tedious occupation, a bit like the worst kind of train-spotting or stamp-collecting. But in Mr. Pastoureau's hands, the symbolic images represented by colors, patterns and animal images open windows into the eccentricities and fancies of men. The Bear By Michel Pastoureau Harvard, 343 pages, $29.95 The theme of "The Bear" is characteristic of its author. As humans become more powerful and more knowledgeable, Mr. Pastoureau argues, they come to devalue the animal world, to discard what their ancestors had respected and venerated. The brown bear is an extreme example of this melancholy decline. Physically the largest and strongest animal indigenous to Europe, the bear was once seen as the king of animal world, just as the African lion is now. Bear pelts were worn to show off a man's strength. Collections of legends were full of heroic encounters between man and bear, fought on almost equal terms. Early cave paintings and grave finds suggest that, among prehistoric communities, the gods were thought to appear in the form of bears. As with most pantheons, worship was born of fear. Fear of bears in early Europe was increased by myths, many with a strong sexual element. Bears were thought of as emblems of lust, abnormally potent, capable of raping women and siring a cross-bred race of heroes. "The border between human and animal," Mr. Pastoreau notes, "was in this instance much more uncertain that the one described by monotheistic religions." Enlarge Image Reunion des Musees Nationaux / Art Resource Byzantine ivory diptych of circus bears. Like many primitive religious beliefs, these persisted well into the Christian era, surviving side by side with the orthodoxies of the Christian church. Hence came the abiding hatred of the medieval church for bears. St. Augustine of Hippo knew little or nothing about them. But he had read his Pliny and, building on the fables of the great Roman naturalist, bequeathed to the medieval centuries the standard Christian image of the bear: malicious, lewd, destructive, predatory. Ursus diabolus est: "The bear is Satan," he wrote. Saints and hermits were frequently described as taming bears, and reducing them to menial servants, in order to show the faithful how the power of God could exorcise the Devil and reduce him to harmless submission. But killing bears was equally worthy, as well as easier for ordinary mortals. Bears were ruthlessly hunted down, although they posed no threat to human communities and their meat was distinctly unappetizing. As a result, bears rapidly disappeared from much of western Europe. At the end of the eighth century, the Emperor Charlemagne organized at least two great bear-hunts in central Europe that resulted in the slaughter of several thousand bears. Enlarge Image Alinari / Art Resource First-century Roman mosaic of a wounded bear; By the 13th century, reports of bear sightings become rare in Europe, as bears retreated to the sparsely populated mountain regions. In the eyes of men, bears ceased to be an object of fear and became a source of entertainment. Itinerant bear-tamers paraded their dancing bears at markets. Kings presented one another with bears to stock their menageries. In 1251, a polar bear arrived in London as a gift from the king of Norway to Henry III of England. According to a chronicler, it was called Piscator (Fisherman), was bathed daily in the Thames River and had its own keeper. Muzzled and chained to avoid accidents, it was regarded as a great spectacle by contemporary Englishmen. As long as men stood in awe of the world of animals, the bear could still arouse respect, especially in the wild. At the end of the 14th century, a duke of Orleans and his friends could still dress up in bear costumes to inspire terror at fancy dress parties. But by the 16th century, the bear's fearsome image was gone. Its strength and potency were forgotten. Noblemen no longer put bears on their coats of arms, and turned to lions instead. Even the traditional association of bears with the Devil had faded away, as smaller beasts like goats, bats and owls displaced them. Enlarge Image Topham / National News / The Image Works Paddington Bear. Our own age has witnessed the ultimate humiliation of the bear. A handful of bears survive in Europe, mostly in the Pyrenees. There are many more in North America, but outside the national parks they too are well on the way to extinction. So far as the bear retains any emblematic status among humans, it is as a toy, symbolic of little more than dumb clumsiness. Winnie the Pooh, in A.A. Milne's fable for children, was a "bear of very little brain," forever being put right by his companion, a donkey if you please. In this, poor Winnie was characteristic of his race. Yogi Bear, another lovable idiot, is not very different. From the king of the mountains and forests to the cloying sweetness of the Teddy Bear, in a millennium. How are the mighty fallen. —Mr. Sumption, a British barrister, is the author of "The Age of Pilgrimage: The Medieval Journey to God." The third volume of his history of the Hundred Years War is "Divided Houses" (2009). Join the discussion 1 Comment, add yours More In Books » facebook twitter linked in Email Print Save ↓ More online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204524604576609443454965846.html

|

|

|

|

Post by warsaw on Aug 18, 2013 3:16:06 GMT -9

www.google.pl/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=9&cad=rja&ved=0CGYQFjAI&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.h-france.net%2Fvol12reviews%2Fvol12no71pluskowski.pdf&ei=HLYQUtDxPIOShQflpoHIDA&usg=AFQjCNHqwl84RMiM7giR1LnFUjs3PxZjhQ&bvm=bv.50768961,d.bGE H-France Review Volume 12 (2012) Page 1 Michel Pastoureau, The Bear: History of a Fallen King. Cambridge and London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2011. 343 pp. Plates, notes, bibliography, and index. $29.95 (cl). ISBN. 978-0-674- 04782-21. Review by Aleksander Pluskowski, University of Reading, United Kingdom. Michel Pastoureau’s book was first published by Seuil in 2007 as L'ours: histoire d'un roi de chu and translated by George Holoch in 2011. Pastoureau is extremely well-known for his prolific work on medieval European visual culture and iconology, in particular on heraldry, animals and colour. His interest in the cultural role of the bear--“the great wild beast of the forest”--stretches back to earlier work, where the transition from pre-Christian to Christian world views was accompanied by the abandonment of traditional animal symbols of power. The bear and wolf were gradually replaced by the lion and eagle. Focusing on the bear, Pastoureau develops this thesis and makes the focus of the book very clear from the onset as the struggle of the medieval Church against the bear and ursine cults, with an emphasis on periods of transition from pre-Christian to Christian societies. Whilst much has been written on the wolf and werewolves, Pastoureau’s work is, to date, effectively unique in adopting such an inter-disciplinary, diachronic perspective. The book is sub-divided into three main sections, followed by a short conclusion and almost a hundred pages of notes, references and indices. The diachronic perspective is very broad, for Pastoureau is moved to begin with the earliest known human-bear relations, with a discussion of select French Palaeolithic sites. After considering representations of bears in cave art, the “ritual” deposit of bear remains in the Chauvet cave and the bear deposit at Le Regourdou, the discussion leaps forward six millennia to the Magdalenian bear sculpture from Montespan. The tone is chatty, even verging at times on flippant and concludes with a suggestion of a connection between prehistoric and historically documented bear cults, asking the question “Why have prehistorians shown so little interest in these cults, which have been solidly documented in historic eras? Why have they never really looked toward the European Middle Ages?” (p. 26). This is somewhat reminiscent of Carlo Ginzburg’s work on the Benandanti, which includes an explicit suggestion of the continuity of pre-Christian practices into the seventeenth century, albeit not one explored in much detail.[1] Both Ginzburg’s and Pastoureau’s work have been incredibly influential (and controversial), defining new approaches to history in the latter decades of the twentieth century. However, these links stretching off into the distant past are not explored in any spatial or temporal depth, partly because there is little or no engagement with material culture as the written record becomes increasingly sparse and fragmentary. As a result these loose and problematic connections continue to draw widespread criticism, especially in the light of studies arguing for multiple discontinuities and reinventions of practices in the past.[2] Pastoureau returns to his notion of the longue durée of ursine veneration throughout the book, for example: “The problem remains for the historian to determine the links that may have existed between possible Palaeolithic bear cults and the cults of antiquity and the High Middle Ages” (p. 37), although he acknowledges the vast gaps in time between these loosely defined chronological episodes. The term “feudal period” is used throughout the book without reference to a specific time range, although when discussing particular case studies precise dating is provided. H-France Review Volume 12 (2012) Page 2 This eclectic use of chronology characterises much of the first section, where the narrative leaps from the Greek goddess Artemis to King Arthur and subsequently from Tacitus to the First Crusade and finally to Old Norse literature. The terms “Celtic” and “German” are widely applied, collapsing the regional nuances that differentiate responses to the bear across Europe during the first millennium AD. When moving onto descriptions of the bear itself, perhaps something that would have been more appropriate at an earlier stage, there is virtually no incorporation of the zooarchaeological data concerning the size and morphology of the European Ursus species, although it is extensive for both prehistoric and early historic Europe. On the other hand, Pastoureau underlines the importance of separating modern and medieval taxonomies, and his discussion of stories of human procreation with bears exemplifies this approach. This perceived proximity to the bear--its closeness to humans--is seen as the main cause for the Church’s hostility towards the species. This leads on to the second section which is concerned with the development of the negative role of the bear from the Carolingian period to the later twelfth century. Here, the defining role of the Church in driving responses to the bear is particularly highlighted. Pastoureau suggests the Church was terrified of bears because of their resemblance to men and argues how the Church’s war against the bear sought to eliminate the physical presence of the animal in the north-western European landscape. He attributes the mass hunting of bears in north Germany and Scandinavia to parallel trends in evangelisation and deforestation, returning to the significance of pre-Christian bear cults. This is an interesting hypothesis which seeks to understand the ecology associated with the process of religious conversion in northern Europe, however relatively little data is provided to substantiate Pastoureau’s claims of a religious war against bears. The concept of a monolithic Church directing a consistent inter-regional response to a single species is problematic in and of itself, particularly when drawing on a suite of disparate commentators. Pastoureau’s point of departure is the eastward expansion of the Carolingian empire. Charlemagne is certainly known for his attempts at ecological management, not only in the case of the bear but also with the establishment of the Louveterie--a corps of professional wolf hunters. The evidence for systematic hunting in Carolingian France and its eastern frontiers is in fact relatively limited, and statements concerning the dwindling numbers of bears from the Ardennes to the Pyrenees are not supported by biogeographical studies, although it is clear bear hunting was practiced by individual aristocrats in many regions of Western Europe. Pastoureau does cite the work of Corinne Beck, without drawing attention to the problematic and uneven distribution of zooarchaeological data at Carolingian sites.[3] Moreover, where the written sources are more complete, Pastoureau provides some interesting vignettes of bear hunting, particularly in the third section where the illustrious counts of Foix are mentioned, but does not situate bear hunting and consumption within broader, regional aristocratic cultures. A brief discussion of the importance of the stag (i.e., red deer) is only found much later. The section concludes with a consideration of the replacement of the bear with the lion as a popular symbol of personal, predominantly elite identity. Pastoureau’s earlier work on heraldry has clearly demonstrated the widespread occurrence of the lion (and eagle) in later medieval European armorials, whilst the use of bears as emblems in parts of Germany and Switzerland is not framed in the form of direct continuity, but rather as the discreet persistence of meanings and the re-contextualisation of symbols within the heraldic vocabulary of Christian society. On the other hand, sweeping statements such as “Slavic and Baltic bears were similarly victims of the inroads of Christianity” (p. 90) are not qualified. It is certainly clear from the archaeology of Late Iron Age/Early Medieval Baltic Europe that the bear played an important role in pre-Christian culture, but this awaits more detailed, synthetic study particularly in terms of the impact of colonisation, the expansion of commerce and Christianisation. H-France Review Volume 12 (2012) Page 3 The third and final section focuses on the debasement of the meaning of the bear from the late medieval period (i.e., the thirteenth century) into the modern day. It begins with a detailed discussion of the bear in the Roman de Renart cycle. Again, the Church is held responsible for associating the bear with vices in the thirteenth century (p. 178). However, there are regular hints of regional diversity. Pastoureau draws on the well-documented lives of Pierre de Béarn and Gaston Phébus, suggesting the bear’s prestige in the Pyrenees was not undermined in the same way as in the north (p. 186), but does not explore this further. Frustratingly, the emblematic use of the bear in German-speaking regions is not included within a discussion of regional variation which disrupts any clear north-south divide. The physical disappearance or rather, the reduction of the populations of bears, in the late Middle Age is linked with the consignment of the species into fictional narratives. The final chapter is concerned with the post- medieval role of the bear, included within a somewhat eclectic discussion of witchcraft, proverbs and the city of Bern. The epilogue leaps ahead to the early years of the twentieth century to the contentious story of the stuffed toy bear--the teddy bear. The final comment of the book is quite abrupt and concerns the inseparable relationship between humans and bears. Overall, Pastoureau’s work is reminiscent of diachronic histories attempting to situate an interesting cultural phenomenon within the full span of human history. It is reminiscent in some ways of Adam Douglas’ The Beast Within, which outlines the patchy cultural history of the werewolf phenomenon.[4] Such approaches are invariably eclectic, partly due to the nature of the evidence--significantly far more sources for the bear are invoked from the twelfth century--combined with the ambitious task of writing a cultural history of any species within a broad European context. Understandably, Pastoureau’s consistent interest throughout the book is the emblematic role of the bear. However, from a methodological perspective, The Bear contrasts with his earlier work on heraldic armorials, which were characterised by a more careful, nuanced and systematic approach. Of course, despite questions posed throughout the book and the enduring theme of the religious war against the bear, there is no claim of direct continuity and the three sections of the book feel somewhat disconnected from each other. There is an implicit assumption of an enduring and consistent relationship with bears until the introduction of Christianity. The central thesis of the book--that the Church was responsible for driving the sustained destruction of the bear--may be attractive from the perspective of Christian iconology but from a holistic perspective is, at present, untenable. This is largely because what is presented is evidence of the conceptualisation of the animal projected within very specific contexts (e.g., bestiaries, beast fables) with no demonstrable link to physical ecology or to forms of wildlife management, as well as regionally and temporally diverse hunting customs which are mentioned but not integrated with the other forms of evidence. What Pastoureau’s book demonstrates very clearly is the variable cultural deployment of the bear by a range of different groups within medieval Christian Europe, from kings, nobles and clerics through to the more corporate monastic and civic communities. It also presents an intriguing hypothesis, although the attribution of the degradation of the natural world to Christian value systems is not new. Perhaps then a more focused, Ginzburgian micro-historical approach would have been better suited to exploring the dual impact of religious and ecological change? But in the absence of the extensive inquisitorial documents which enabled Ginzburg to reconstruct the minutiae of the world of his protagonists, a study focusing on a more intangible agent such as the bear requires a wholly inter-disciplinary approach drawing on many lateral strands of evidence. If successful, it would have provided a more detailed context for responses to the bear, without an overwhelming focus on the species itself. This context is not wholly absent from Pastoureau’s synthesis, but it is incomplete and often erratically presented. H-France Review Volume 12 (2012) Page 4 Overall, Pastoureau’s The Bear is a fascinating collection of evidence pertaining to various aspects of the bear and a veritable mine of information, but it is far from a systematic and careful study which incorporates the broadest body of data. Its central tenets are not convincingly argued and despite the suggested emphasis on ecology and the relationship between the physical and conceptual animal, there is a noticeable absence of zooarchaeological and environmental data. This is certainly mentioned, but not truly integrated. Pastoureau would make no apologies for this and his book is very much presented as a thoughtful and controversial thesis, a seminal work of cultural history which aims to provoke further discussion, and in the process, develop our understanding of one of the most important species repopulating the modern European landscape. NOTES [1] Carlo Ginzburg, The Night Battles: Witchcraft and Agrarian Cults in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1983) (first published in 1966 as I Benandanti: Stregoneria e culti agrari tra Cinquecento e Seicento). [2] One of the most prolific writers on these discontinuities is Ronald Hutton, particularly his The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy (Oxford: Blackwell, 1993). [3] Christopher Loveluck, “Rural settlement hierarchy in the age of Charlemagne”, in Joe Story ed., Charlemagne: Empire and Society (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005) pp. 230–258, at pp. 251–252. [4] Adam Douglas, The Beast Within: Man, Myths and Werewolves. London: Orion, 1993. Aleksander Pluskowski University of Reading, United Kingdom a.g.pluskowski@reading.ac.uk Copyright © 2012 by the Society for French Historical Studies, all rights reserved. The Society for French Historical Studies permits the electronic distribution of individual reviews for nonprofit educational purposes, provided that full and accurate credit is given to the author, the date of publication, and the location of the review on the H-France website. The Society for French Historical Studies reserves the right to withdraw the license for edistribution/republication of individual reviews at any time and for any specific case. Neither bulk redistribution/ republication in electronic form of more than five percent of the contents of H-France Review nor re-publication of any amount in print form will be permitted without permission. For any other proposed uses, contact the Editor-in-Chief of H-France. The views posted on H-France Review are not necessarily the views of the Society for French Historical Studies. ISSN 1553-9172

|

|

|

|

Post by warsaw on Jul 18, 2015 22:06:44 GMT -9

The Chronicle Review Comments (14) November 27, 2011 Our Animals, Ourselves Our Animals, Ourselves 1Jason Holley for The Chronicle Review By Justin E.H. Smith When I was very small I lived on a defunct chicken farm. There was a house with a yard, and these together took up half an acre. To the north there was a long, thin chicken coop, empty of chickens, and behind it lay the back pasture, which occupied one acre. Perpendicular to this, to the west, there was the side pasture. Steers dwelled in the back pasture, ate hay, shat, sculpted odd forms on the salt lick (until we had them shot and butchered). As far as I know, these were actually existing steers. But the side pasture was inhabited, I imagined for a long time, by a fox. When I went there by day, I felt I was entering upon its territory; and when I lay in bed at night, I was certain it was out there, in its burrow, dwelling. It lived there like a human in a home, and was as real as any neighbor—except that I had myself brought it into existence, likely by projecting it out of a picture in a book. The fox did not need to exist in order to function in my imagined community, one which must be judged no more or less real than that of, say, Indonesians, or of humanity. It was enough that there be foxes at all, or creatures that fit that description, in order for me to conjure community with the imaginary fox in the side pasture. And it was no mere puerile phantasm that caused me to imagine this community, either. It was rather my thinking upon my own humanity, a condition which until very recently remained, over the course of an entire human life, embedded within a larger community of beings. These days, we are expected to grow out of that sort of thinking well before puberty. Our adult humanity consists in cutting off ties of community with animals, ceasing, as Lévi-Strauss put it, to think with them. When on occasion adults begin again to think about animals, if not with them, it is to assess whether animals deserve the status of rights-bearers. Animal rights, should there be such things, are now thought to flow from neurophysiological features and behavioral aptitudes: recognizing oneself in the mirror, running through mazes, stacking blocks to reach a banana. But what is forgotten here is that the animals are being tested for re-admission to a community from which they were previously expelled, and not because they were judged to lack the minimum requirements for the granting of rights. They were expelled because they are hairy brutes, and we learned to be ashamed of thinking of them as our kin. This shame only increased when Darwin confirmed our kinship, thus telling us something Paleolithic hunters already knew full well. Morality doubled up its effort to preserve a distinction that seemed to be slipping away. Since the 19th century, science has colluded with morality, always allowing some trivial marker of human uniqueness or other to function as a token for entry into the privileged moral universe of human beings. "They don't have syntax, so we can eat them," is how Richard Sorabji brilliantly reduces this collusion to absurdity. RELATED CONTENT Fauna Fealty Enlarge ImageOur Animals, Ourselves 2 Enlarge ImageOur Animals, Ourselves 3 Before and after Darwin, the specter of the animal in man has been compensated by a hierarchical scheme that separates our angelic nature from our merely circumstantial, and hopefully temporary, beastly one. And we find more or less the same separation in medieval Christian theology, Romantic nature poetry, or current cognitive science: All of it aims to distinguish the merely animal in us from the properly human. Thus Thoreau, widely lauded as a friend of the animals, cannot refrain from invoking animality as something to be overcome: "Men think that it is essential," he writes, "that the Nation have commerce, and export ice, and talk through a telegraph, and ride 30 miles an hour, without a doubt, whether they do or not; but whether we should live like baboons or like men, is a little uncertain." What the author of Walden misses is that men might be living like baboons not because they are failing at something or other, but because they are, in fact, primates. Thoreau can't help invoking the obscene and filthy beasts that have, since classical antiquity, formed a convenient contrast to everything we aspire to be. The best evidence suggests that this hatred of animals—there's no other word for it, really—is a feature of only certain kinds of society, though societies of this kind have dominated for so long that the hatred now appears universal. Until the decisive human victory over other predatorial megafauna several thousand years ago, and the subsequent domestication of certain large animals, the agricultural revolution, the consequent stratification of society into a class involved with food production and another, smaller class that traded in texts and values: Until these complex developments were well under way, human beings lived in a single community with animals, a community that included animals as actors and as persons. In that world, animals and human beings made up a single socio-natural reality. They killed one another, yes, but this killing had nothing in common with the industrial slaughter of domestic animals we practice today: Then, unlike now, animals were killed not because they were excluded from the community, but because they were key members of it. Animals gave themselves for the sake of the continual regeneration of the social and natural order, and in return were revered and treated as kin. As human beings abandoned community for domination, thinking with animals became a matter of symbolism. Bears showed up on coats of arms, for example, not because the warriors who fought behind these shields were fighting as bears, as magically transformed ursine warriors. They were fighting behind the bear shield simply because that's what their clan chose, as today one might choose Tasmanian Devil mudflaps for one's truck. It was an ornament, a mere symbol. Or was it? The eminent medieval historian Michel Pastoureau's recent book, The Bear: History of a Fallen King (Harvard University Press), is motivated by a conviction that the symbolic is never merely symbolic, that when mythological elements are transformed into literary motifs, or totems into coats of arms, this does not mean that the old way of looking at things is entirely forgotten. Accordingly, Pastoureau believes that animals continued to shape our view of social reality well into what I have been calling the era of domination. Pastoureau's choice of research focus was widely dismissed as childish when he took it up in the 1970s: It is children who pay attention to Mr. Fox and Mr. Bear, the French historical establishment declaimed. Adults should turn their attention to adult matters—which is to say human matters. The bear accordingly grew plush, diminutive, and migrated to the crib in the form of the teddy bear. This destination serves as the end point of Pastoureau's study, and while this chapter of the bear's social history is not nearly as interesting as its medieval incarnation (or its Paleolithic one), it does serve to illustrate how far the king of European beasts has fallen. Falling, humiliation, abasement: This is the story Pastoureau wants to tell, of a creature that was, in pre-Christian Europe, an exalted double of the human warrior; that in the high Middle Ages was displaced by the lion as the king of beasts; and that by the modern period was best known as a broken, muzzled circus curiosity. By the 14th century, the bear would be "forced to obey not saints or heroes but a mere jongleur or a vulgar animal showman with a monkey on his shoulders or hares popping out of his clothing." Yet throughout its fall into dishonor, Pastoureau believes, the bear remained one of us: Even when it is abased, we see not some poor creature; we see what could easily be our own fate as well. That we see ourselves in the bear in a way we would not in, say, a spider, is a result of what is often called anthropomorphism. It's important to distinguish between a relatively wide and a relatively narrow sense of this concept. Broadly speaking, traditional societies were inclined to anthropomorphize all animals, to the extent that they attributed intentions and interests to spiders, fish, deer, etc. But pre-modern Europeans, according to Pastoureau, anthropomorphized the bear in a narrower sense: It really was given the "form of man," construed as a special kind of man, as a creature not just with ursine interests of its own, comparable to arachnid interests, ichthyoid interests, and so on, but with distinctly human interests. These interests extended right down to the choice of mates, which for male bears were, ideally, human women. As the ultimate mark of kinship, such couplings were thought to be perfectly fertile. Half-bear offspring were held to be particularly virile and heroic, and for this reason bears often show up in royal lineages. The 12th-century Gesta Danorum casually notes that the Danish king is descended from a bear, an observation that is repeated as late as the 16th century in the work of Olaus Magnus. This is not mythology, but straightforward genealogy, and there is no indication that it was doubted by the authors who promulgated it. While a human male cannot couple with a she-bear, there is another way a human might end up with an ursine mother: adoption. A she-bear not only takes care of an abandoned human infant by bringing it food, but also nurses it with her milk and, most importantly, licks it, literally, into shape. It is this licking that was believed to transform cubs from mere unformed masses of hair—what in the Aristotelian zoological tradition would have been called moles—into proper beings. Milk-giving and licking are nearly as powerful a means of transmitting kinship as sperm (in many cultures, two children who drink milk from the same wet nurse are considered siblings), and it is in this way that a human can have a bear as either a mother or a father. Another way is through magical transformation, perhaps by drinking the blood of a bear, or by covering oneself in a bear's hide. Many will know already of the Scandinavian Berserkers, literally, the "bear shirts," who "went into battle imitating the gait and the groans of the bear." Pastoureau notes that according to some sources, the Berserkers "ate human flesh; still others [report that] they were metamorphosed into bears in the course of a magical-religious ceremony in which cries, chants, dances, potions, and drugs brought them to a state of frenetic excitement, as though they were possessed." Until the 10th century, European men from the North Sea to the Pyrenees transformed themselves into bears to enhance their experience of sex and violence. The end of the bear's hibernation in early February was marked by "songs, dances, games, and ursine masquerades." Many tales also tell of bears—not just lads dressed as bears—falling in love with women, kidnapping them, raping them, and forcing them to live as wives. The virility and violence so strongly associated with the bear made it suspicious to the church. By the high Middle Ages the ecclesiastical authorities had succeeded in deposing it, reducing it to a pathetic circus performer. At the same time, the church succeeded in enthroning the lion in the bear's former position in heraldry and more broadly in the medieval symbolic imagination. The lion was a safe choice as king of the beasts in large part because it was entirely extinct in Europe. It was no longer phenomenally salient in the daily lives of European folk, indeed hadn't been for millennia, and so there could be no threat of dangerous effects from consuming its parts, from wearing its hide, or from having sex with it or as it. No young man could think to transform himself into a lion in order to ravage a village girl. "The foreign lion," Pastoureau writes, "preferred by the medieval Church, gradually drove [the bear] off, demonstrating that ... cultural history always wins out over natural history. Or, more precisely, ... natural history is simply one branch of cultural history." By the late Middle Ages the lion, while non-native and physically absent, had become "a part of daily life" for average Europeans, which "raises a question for the historian about the aptness of the now familiar opposition between 'native' and 'exotic' animals. For feudal societies, the lion was not really an exotic animal, even though it had not been native to Europe for several millennia. The lion could be seen every day and everywhere, represented on a great many monuments, objects, precious fabrics, and works of art." Established for millennia as king of the beasts in literate Asian and Middle Eastern traditions, the lion was easy to import as a symbol, particularly in the era of the Crusades, as Jerusalem came again to be conceptualized as the center of the world. What better title to show up there with than "Lion-Hearted"? For the most part, the church was successful in dethroning the bear, but one senses that the shift in symbolism had at least something to do with ecological history as well as the history of ideas. Today, the bear is more or less extinct in France (and England, and the Low Countries), other than in parts of the Alps and the Pyrenees. The worship of the bear seems to have diminished in rough correspondence to its geographical disappearance over the centuries. (The lion could be maintained as king without being geographically present, but only by a top-down campaign.) Today Romania has by far the highest concentration of bears in Europe (thanks in part to Nicolae Ceausescu's promotion of bear fertility—a policy derived entirely from his personal interest in accumulating hunting trophies), and is also the place you are most likely to see vestiges of the jocum cum urso (now evolved into the Latinate jocul ursului, or "game of the bear") that was already on the decline in France by the ninth century. To "play the bear" is to allow one's animal nature to come to the surface. On the standard interpretation of Christian anthropology, this is a nature that, while ineradicable, must be kept in submission. Yet Pastoureau argues that even within the Christian tradition there was a double movement: Our own animality was to be detested, yet animals, as testimony of God's majestic creation, were nonetheless to be revered. St. Paul and the earliest church leaders tended to see animals as worthy of love, but it was above all Augustine who established the general sentiment of zoophobia that would predominate in the centuries to come. For Augustine, both difference from humans as well as similarity to humans seemed sufficient ground to deem animals diabolical. Bears, for example, were particularly troubling because they, so it was thought, copulated face to face, just like humans. For Augustine, "who was continually asserting that man and beast could in no way be confused with one another, that human and animal nature were completely different, this was a scandal, a crime, a transgression of the order intended by the Creator, something truly diabolical: 'ursus est diabolus.'" Cicero quotes a line from the poet Ennius: Simia quam similis turpissima bestia nobis: 'How like us is the ugly beast, the ape.' In fact, this is just one instance of a general rule concerning human perception of what are sometimes called higher animals, and when Ennius was writing, the worst had not yet begun for the other primates. As Pastoureau comments, the major monotheist religions "do not like animals that nature and culture have declared to be 'cousins' or 'relatives' of man. The pig"—about which Pastoureau has written a separate study, Le cochon: histoire d'un cousin mal aimé—"was a victim of this in biblical Antiquity. The bear suffered in turn in the heart of the Christian Middle Ages. And the great apes suffered the same fate a few centuries later. It has never been a good idea to resemble human beings too closely." On July 26, 2011, The Independent reported that "A mystery animal which has been attacking sheep in the Vosges since April has been identified by a remote-control camera as a wolf." In the 18th century such a mystery could not be so easily dispelled, and when a series of attacks took place in the Gévaudan region of France in the 1760s, mostly on peasant girls, rumors began to fly. The simplest explanations were generally passed over in favor of ones involving supernatural forces, implausibly large creatures, or anatomically impossible hybrids. By the time the killing came to an end in the winter of 1765, a full-fledged legend had been born, one that would give rise to generations of amateur sleuths, and even, in 1889, to a Roman Catholic demonological treatise on the supposed monster. Jay M. Smith's recent book, Monsters of the Gévaudan: The Making of a Beast (Harvard University Press), like Pastoureau's work on the bear, concerns a fierce European animal, but in any more profound sense the two books have little in common. Smith's subject is the human reaction to a mysterious specter. Pastoureau's by contrast is very much a known commodity, and even when it is not precisely known, even when the facts about it are all a bit off, it is nonetheless conceived as a familiar, as a neighbor. The wolf has had a very different history in Europe than the bear, as Pastoureau himself notes. "Fear of the wolf," he writes, "a major factor in peasant sensibility, is linked to crisis periods (climatic, agricultural, social), not to times of economic prosperity or demographic expansion. It was not accidental that the story of the beast of the Gévaudan took place in the France of the 18th not the 13th century. In the French countryside in the feudal period, people feared the Devil, dragons, the Wild Hunt, and night hunting, but not really the wolf." Smith's book is indeed that of an 18th-century specialist seeking to reveal through microhistory the hopes and fears of the Gévaudan peasants. In doing a microhistory of the events behind a folk legend, Smith has taken on an extremely difficult task. He is interested in an occurrence that has long been mired in amateur cryptozoological lore, but wishes to treat it in terms of the "cultural and psychological depths" of the 18th-century French villagers. Smith aims to "shift attention away from the beast itself." Occasionally, this new approach leads Smith to write as though he were trying to impress a tenure committee or a grant-making organization: "I examine all the available sources in close detail in order to break through the ossified discourses that have long surrounded the beast's tale," and so on. That is not entirely fair to the discoursers. Some local French Web sites dedicated to the beast are amateurish indeed, but there is nothing at all ossified about them: They are lively and amusing. Now I too have little patience with cryptozoology, though I admit I am an adept of what might be called metacryptozoology: reflection upon the reasons why people need to imagine there are more creatures out there than there in fact are. I assume that the beast of the Gévaudan was just a very hungry wolf. But why it is that species are multiplied in the human imagination beyond strict necessity remains an interesting question, and a universal one that extends far beyond the Gévaudan in the 18th century. In general, one senses that Smith, unlike Pastoureau, is not all that interested in winning for animals their own history. Smith is interested in the "popular beliefs, scientific thought, religious tensions, media markets, aristocratic culture," and so on, of human beings, and animals real and imagined occasionally enter into this. Pastoureau, by contrast, has written a history of a symbiosis. I personally would like to see a treatment of the wolf comparable to Pastoureau's of the bear: one that takes seriously the proposition that the beast of the Gévaudan and the people of the Gévaudan have a shared history, rather than the former simply being an imposition upon the latter, which afterward echoes within their distinctly human cultural and psychological depths. When I was little, I went camping with a friend who liked to freak everyone out. He told a story of a man who had been hiking, and came upon a zone of friable rock. When trying to climb across it, he slipped right through, and landed in an underground cavern. He was pulled out after some hours or days, but what was in fact retrieved was no longer the camper who fell in, but only a mute, blubbering madman. He had seen something down there. I asked my friend what it was. My friend didn't know. No one knows, he added ominously. I assumed that the man must have witnessed some sort of blending of the human and animal worlds, a blending you are not supposed to see: not one that is simply "gross," as we might have said back then, but rather one that cannot be espied without the basic order of the universe collapsing. What could that have been? Bears and humans copulating? Bears and humans feasting together on less fortunate humans? No, I found I could think all of this, and come out more or less all right. It must have been something far worse, a secret ursine transformation, a "becoming animal," so to speak, in which everything that Augustine and his successors sought to keep in check comes erupting uncontrollably to the surface, not out of any intentional invocation, such as the Berserkers performed, but out of a complete loss of human self-mastery. This is, I take it, a very deep human fear, certainly deep enough to freak out a 10-year-old. The fear of the beast in the secret cavern—the bear that would animalize the soul of any human being who happened into its lair—exists side by side and in tension with my imagined community of the gentle fox in his burrow in the side pasture. The hairy beast in the cavern, the bear that does unspeakable things to the maiden it abducts, the wolf that dresses up as a grandmother in order to eat/rape Little Red Riding Hood: These are the ne plus ultra of enmity, the very opposite of community. Traditionally, hunters offered up incantations and sacrifices, and took other such measures to keep the community as extensive and stable as possible, to extend it to the other top carnivores as well as to the gentle beings, without forgoing bloodshed in order to do this. It was a community not defined by species, and not based upon a social contract that precludes killing. Killing resulted in eating, and thus in absorbing the other's powers: perhaps in the end a more profound form of community than living and letting live. This is the sort of community human beings once co-inhabited with bears and wolves, before these hairy cousins of ours were assimilated to the Devil. Justin E.H. Smith, an associate professor of philosophy at Concordia University, in Montreal, is author of Divine Machines: Leibniz and the Sciences of Life (Princeton University Press, 2011). He is at work on a book about human nature and human difference. chronicle.com/article/Our-Animals-Ourselves/129873/ |

|

|

|

Post by warsaw on Oct 19, 2015 2:44:54 GMT -9

The Bear – History of a Fallen King – The Historian Considers the Animal.

Was Charlemagne the greatest enemy to the bear that Europe ever knew? Massacres of the beast were so numerous during his reign that the historian is entitled to pose the question. On two occasions in Germany the massacres took on a systematic character, in 773 and 785, both times after victorious campaigns against the Saxons. The future emperor, of course, never killed a bear with his own hands, even though he was, according to the chroniclers, a formidable huntsman, but soldiers acting on his orders conducted very large battles in the forests of Saxony and Thuringia.

The bear’s enemies were not in fact so much Charlemagne and his troops as the prelates and clergy around them. The church had declared war on the strongest animal on European soil and was determined to exterminate it, at least on German territory. There was a particular reason for this: In all of Saxony and the neighboring regions in the late eighth century, the bear was sometimes venerated as a god, which gave rise to forms of worship that were sometimes frenetic or demonic, particularly among warriors. Bears had to be absolutely eradicated to convert these barbarians to the religion of Christ. It was a difficult, almost impossible task, because these cults were neither recent nor superficial. They certainly pre-dated the Roman period – several Latin writers had already alluded to them – and were still present in the German heartland in the Carolingian period.

Following Tacitus, historians have written a good deal about the religious practices of the ancient Germans. They have all emphasized the German’s veneration for the forces of nature and described ceremonies associated with trees, stones, springs, and light. Some places were reserved for divination or the adoration of idols; others were used for huge assemblies at specific times ( new moon, solstice, eclipse ); still others were notable burial sites. Everywhere, rituals involving the use of fire and blood paid homage to various divinities. Dancing, trances, masks, and disguises were frequent. Bishops and their missionaries did not find it easy to put an end to these practices. They gradually succeeded by replacing sacred trees and springs with Christian places to worship, then by transforming a large number of pagan gods and heroes into saints, and finally by blessing or sanctifying most daily activities. But this Christianization remained uneven for a very long time, and it wasn’t really until after the year 1000 that the last remnants of the old religion disappeared.

While modern historians have written extensively about the worship of trees and springs, they have had much less to say about bear worship, as though it had been negligible or confined to certain tribes. But this was not the case. As chronicles and capitularies clearly attest, bear worship was widespread in both Germany and Scandinavia. It was denounced early on by several missionaries who had ventured well beyond the Rhine. In 742, for example, Saint Boniface, on a mission to Saxony, wrote a long letter to his friend Daniel, Bishop of Winchester, in which he mentioned among the “appalling rituals of the pagans” the practice of disgusting oneself as a bear and drinking the animal’s blood before going into battle. Thirty years later, in an official list prepared by prelates of the pagan superstitions of the Saxons to be combatted, the same practices were again denounced, along with others that were even more barbaric.

These customs were nothing new. From time immemorial the bear had been a particularly admired creature throughout the Germanic world. Stronger than any animal, it was the king of the forest and of all the animals. Warriors sought to imitate it and to imbue themselves with its powers through particularly savage rituals. Clan chiefs and kings adopted the bear as their primary symbol and attempted to seize hold of its powers through the use of weapons and emblems. But the Germans’ veneration for the bear did not stop there. In their eyes, it was not only an invincible animal and the incarnation of brute strength; it was also a being apart, an intermediary creature between the animal and human worlds, and even an ancestor or relative of humans. As such, many beliefs collected around the bear and it was subject to several taboos, particularly with respect to its name. In addition, the male bear was supposed to be attracted by young women and to feel sexual desire for them: it often sought them out, sometimes carried them off and raped them, whereupon the women gave birth to creatures that were half man and half bear, who were always indomitable warriors and even the founders of prestigious family lines. The border between human and animal was in this instance much more uncertain than the one described by monotheistic religions.

In the eyes of the Church, all of this was absolutely horrifying, all the more because worship of the great wild beast of the forest was not confined to the Germanic world. It was also found among Slavs and to a lesser extent among Celts. The Celts, of course, had been Christianized for several centuries, and their old animal cults had gradually adopted discreet forms, surviving primarily in poetry and oral tradition. But this was not true of the Slavs, and they admired the bear as much as the Germans did. Indeed, in a large part of non-Mediterranean Europe in the Carolingian period, the bear continued to be seen as a divine figure, an ancestral god whose worship took on various forms but remained solidly rooted, impeding the conversation of pagan peoples. Almost everywhere, from the Alps to the Baltic, the bear stood as a rival to Christ. The Church thought it appropriate to declare war on the bear, to fight him by all means possible, and to bring him down from his throne and his altars.

The struggle of the medieval Church against the bear forms the central section of this book. Undertaken very early, even before the reign of Charlemagne, it lasted for nearly a millennium, through the High Middle Ages and the feudal period, coming to an end only in the thirteenth century when the last traces of the ancient ursine cults disappeared and throughout Europe an exotic animal from eastern tradition, the lion, definitively seized the title of king of the animals, until then held by the bear.

highlights of chapter one – ‘The First God?’

The oldest trace of the symbolic ties between man and bear seems to date from approximately 80,000 years ago in P’erigord, in the cave of Regourdou, where a Neanderthal grave is connected to the grave of a brown bear under a single slab between two blocks of stone, thereby indicating the special status of the animal.

Beginning with the Upper Paleolithic, approximately 30,000 years ago, evidence becomes more plentiful and solid, showing how in some regions and in certain periods men and bears inhabited the same territories, frequented the same caves, hunted the same prey, struggled against the same dangers, and probably had both economic and symbolic relations with one another. For that period, everything seems to confirm that the bear was no longer considered an animal like other animals, that it occupied a special place between the worlds of beasts and men, and that it may have served as a mediator with the beyond. Does this mean it is legitimate to say there was a prehistoric cult of the bear, practiced in several regions of the northern hemisphere in the Paleolithic period? The question provoked, and continues to provoke, passionate controversy among prehistorians.

In both wall art and portable art, in any event, the bear is represented in a greater variety of postures than any other animal. It is also always the animal with the most stylized, schematized design. It is well known that in historical time, the simplification of forms in the representation of an animal is generally proportional to the place the animal occupies in the world of symbols. Was this already the case in the Paleolithic? The bear, finally, is the only animal represented full face in clay modeling ( bringing together both full-face and profile views ) as well as painting and engraving.

Immune to fear and danger, bears regularly frequented caves over dozens of millennia: the brown bear in summer, for coolness and rest; the cave bear in winter, for hibernation and the birth and early care of its young. Bears were, of course, not the only animals that frequented caves, but they did so more often and, significantly, in larger numbers than the others. In the oldest sites, 80 to 90 percent of the bones found belong to bears, and in so0me cases the figure reaches 100 percent. Two such examples are Cueva Eiros in Spain and Dijve Babe in Slovenia, where, in addition, the quantity of bones and bone fragments is considerable. Even larger quantities of bone and bone fragments are located in the cave of La Balme-a-Collomb at the foot of Mount Granier in the Massif de la Chartreuse in France. In 1988, skeletal remains were found there probably belonging to several thousand Ursidae. The site has not yet been completely inventoried, but it is possible that this number will exceed three or four thousand. Carbon 14 dating has established that bears frequented this cave over a period of more than twenty thousand years, from 45,000 to 24,000 BC.

Even more than bones and fragments of bones, skulls were subject to particular treatment: skulls deliberately covered with a mound of clay; skulls artistically piled in stone hollows; skulls set in fissures or cavities sealed by dry stones forming sorts of chests or tabernacles; skulls with the lower jaw removed and run through with a femur, a tibia, or a penis “bone”; skulls arranged in a circle or semicircle on the floor around a larger raised skull; finally, skulls set in the center of a chamber on a rocky promontory forming something like an alter. Most of these arrangements seem to be clearly ritual in nature and encourage researchers to describe them using terms borrowed from liturgical vocabulary. In every case they encourage looking at the bear as a creature apart, intermediary between the world of animals and the world of the gods. Indeed, one encounters similar evidence for no other animal.

Several researchers have taken that step, some of them early on, relying both on the evidence just mentioned – images, skulls, bones, locations, and arrangements – and on ethnological comparisons with societies that until recently practiced the cult of the bear, and sometimes even continue to do so. They include the Ainu in Japan and Sakhalin; various native peoples of Siberia such as the Ostyaks, the Evenks, and the Yakuts; the Lapps in Scandinavia; and the Inuit in Canada and Greenland. In historic time, the cult of the bear, in one form or another, has been thoroughly substantiated in several northern hemisphere societies and has been the subject of investigations and publications. Does this mean it is legitimate to go back millennia and project onto societies of the Paleolithic much more recently documented beliefs and rituals? Some prehistorians believe that it is and, combining evidence and comparisons, have confirmed the existence of a paleolithic religion of the bear, perhaps connected to specific hunting techniques, the ritual deposit of the skull and bones of the animal that had been killed, and to the fabrication of tools from the bones of cave bears.

The animal most abundantly represented in the Chauvet cave is not the bear but the rhinoceros, forty-seven examples of which have been counted so far; next come cats and mammoths, with thirty-six each. However, the twelve images of bears that can be seen on various walls are the most numerous ever found in a single cave. They are remarkable in their imposing size, firm outline, and red or black color. Most important, they seem to echo the many vestiges left by bears who had lived in the cave: scratches, traces of fur and rubbing, paw prints on the walls and the floor ( including those of a she-bear and her cub ), trails, hollows and depressions trapped in the clay, very numerous bone remnants, and a collection of at least 150 skulls. This cave does indeed “smell of bear,” perhaps more than any other.

But it does more than that. It puts the bear on a stage and, more than anywhere else, it seems to make it an animal worthy of veneration: in the center of a circular chamber from which all bones, fragments of bones, and anything else movable was removed, a large skull is set on a block of stone with a flat surface resembling an alter; on the floor around it several dozen other skulls are arranged in a circle. This was obviously a stage setting, not the work of bears or the consequence of geological or climatic accidents, but clearly due to voluntary human action.

*Note: several of the Greek myths concerning bears are told in this book. I will post one of them: Daughter of King Lycaon of Arcadia, Callisto was extraordinarily beautiful but avoided all men. She preferred to hunt in the company of Artemis, because, like the goddess herself and all her followers, she had made a vow o0f chastity. Zeus saw her one day and became infatuated; to approach her, he took on the form of Artemis and forced himself upon her. The young woman became pregnant and the time came when she could no longer conceal it. Violently angry, Artemis shot her with an arrow, which immediately delivered her of the child and also transformed her into a she-bear. Thereafter she wandered in animal form in the mountains while her son Arces grew up to become the king of Arcadia. One day out hunting he encountered his mother, still in the form of a she-bear. He was about to kill her when Zeus, to avoid such a crime, changed him too into a bear, or rather a bear cub; then he lifted them both into the heavens, where they became the constellations Ursa Major and Ursa Minor.

In other versions, Callisto was the vivtim of Hera’s anger, not that of Artemis. And it was the wife of Zeus who changed her into a she-bear; once Zeus had saved the animal and made her into the northern constellation, Hera asked Poseidon to prevent her from ever sinking into the ocean. That is why Ursa Major and Ursa Minor are the only constellations that always remain above the horizon.

At one point or another in its history, every culture chooses a “king of the beasts” and makes it the centerpiece of its symbolic bestiary. Forms of expression, oral traditions, poetic creations, and insignia and representations of all kinds grant the chosen animal superiority over all others and a central place in belief systems, forms of worship, and rituals. Despite the extremely diversity of societies, it can be said that the choice almost always derives from the same criterion: the designated animal is chosen because of irs reputation, justified or not, for invincibility. Everywhere and always, the king of the beasts is the one who cannot be conquered by any other animal. The very few exceptions are circumstantial or are based on systems of reversal that merely confirm the criterion: choosing as king the weakest or most fragile animal still relies on the essential notions of strength and victory. And such instances are trivial, because the general rule, seldom infringed, is that the king is always the strongest.

This means that choices are restricted. In Africa, it is sometimes the lion, sometimes the elephant, less frequently the rhinoceros; in Asia, the lion, the tiger, or the elephant. In America, the choice falls on the eagle or the bear, and, in regions where it can be found, the jaguar. In Europe, the king was for a long time the bear, and later the lion. There have been occasional scattered variants, but they are limited in time or space, whereas a “true” king of the beasts has to last and flourish in several different cultural regions. With this in mind, looking at the entire planet, there are, so to speak, only four kings of the beasts: the lion, the eagle, the bear, and the elephant. Each of them holds or held that rank not only in its place of origin but also sometimes in other cultures and on several continents. This is particularly true of the lion, which, already the king in Asia and Africa, slowly took the place of the bear in Europe.

The Herculean strength of the bear, the fact that no animal can best it ( man is its only predator ), and its long history of being admired and feared in all European regions were not enough to keep it on its throne. The foreign lion, preferred by the medieval Church, gradually drove it off, demonstrating that, despite the criteria set out above, cultural history always wins out over natural history. Or, more precisely, as I noted at the beginning of this book, natural history is simply one branch of cultural history.

No animal indigenous to Europe gave an impression of strength comparable to the bear’s. All the ancient authors who wrote about the animal emphasized this impression, and it gave rise to many proverbs, images, and metaphors. The expression “strong as a bear” exists in all European languages and matches a reality already described by Aristotle in his ‘History of Animals’ and adopted by all his imitators and successors, notably Pliny and the medieval tradition he gave rise to. The bear was the strongest of all the animals in Europe. Subsequently, modern naturalists from Gesner to Buffon explained what made up that strength, where it came from, and how it manifested itself. And although nineteenth-and-twentieth-century naturalists contributed some supplementary incidental information, they hardly changed a picture that was already well established by the time of the Renaissance.

The brown bear appears first of all as a powerful and massive creature that could reach a height of eight or nine feet and a weight of 600, 800, or even 1000 pounds. Those are, of course, record figures, at least in Europe, but it is likely that ancient and medieval bears were heavier than their present-day descendants. The bear is fattest in late autumn, when it begins hibernation. Its heavy look and clumsy appearance are accentuated by a short, thick neck of extraordinary strength and a very broad chest. Neck and chest contrast with a relatively small head and modest hindquarters. The animal’s primary strength is located in the muscles of the neck, shoulders, arms, and chest. It resembles a stocky wrestler with a disproportionately large upper body. This is confirmed by anatomic analysis of its musculature, which reveals very powerful brachial, dorsal, and pectoral muscles. They are what enable the bear to carry or haul loads heavier than itself, to move gigantic blocks of stone, to break huge tree trunks, to kill a man or a large animal – cattle or wild game – with a single blow of a paw.

Despite the disproportionately small size of its head compared to its chest, the bear has very well-developed masticatory and temporal muscles. They are associated with a versatile and effective dental apparatus adapted to its omnivorous diet. First, there are incisors that are veritable pincers, enabling the animal not only to cut almost anything but also to grasp farm animals ( sheep, goats, pigs ) and carry them in its mouth. The canines are fearsomely sharp, and with them it lacerates and tears its prey to pieces. Finally, huge molars enable it to grind any vegetable and extract fruits from their shells. But the small size of the jaw opening means that it makes less use of its teeth than of its forepaws, particularly the left one, which it sometimes uses as a club, to attack and kill. Two writers, one medieval and the other modern, have noted that the bear uses its left more often than its right paw and concluded – a bit too hastily – that it was “left-handed,” a particularity which, added to many others, seemed to strengthen its troubling, not to say harmful character. Earlier cultures, notably the Christian culture of the Middle Ages, saw left-handedness as the sign of an evil nature, or indeed of a counter-nature.

To its extraordinary muscular strength, the bear adds resistance to fatigue and to bad weather unmatched by any other European species. The bear seems not to be troubled by cold, rain, snow, wind, or storm; only extreme heat reduces its activity and impels it to rest. But bears generally seem to overcome all the hostile forces of nature and to look on any form of danger wit contempt. No animal frightens them, not even the largest boars they encounter in the woods and that sometimes battle with them over prey, and even less the packs of wolves that attack bears in winter in groups of fifteen or twenty and try to tear them to pieces. The bear fears nothing and is, indeed, practically invincible.

They had long known of the existence of the large manned cat, the huge pachyderm, and a few other exotic animals remarkable for their size, their power, or their appearance. The Romans in particular had been able to marvel at the physical presence of various species in the circus games that were larger and more savage than the European bear. Although they sometimes staged battles in the arena between bears and bulls ( the bears almost always won ), they especially liked to see wild animals brought from Africa or Asia fight one another or against men. Sometimes, however, curiosity made them wonder about the strength of a bear or a bull compared to that of an animal from afar, and so there were battles between bears and lions, bears and panthers, bulls and lions, bulls and an elephant, and even a bear and a rhinoceros. Although bulls, fighting alone or in a group, seem never to have been victorious, a bear always won in single combat against a lion or against several panthers. But that was not enough to make the bear the king of the beasts in the eyes of the Romans. Like the Greeks – who had little fondness for animal combat – they preferred to install on the throne either the lion or, perhaps more frequently, the elephant. There never seems to have been a battle between a bear and an elephant, but Martial recorded a combat in Rome late in the first century of our era between a bear and a rhinoceros: the latter won easily, piercing the bear’s stomach with its horn, then lifting its wounded opponent from the ground with its snout and tossing it in the air several times. A cruel humiliation for the European champion.

Aside from this battle, bears usually won glory in circus games. They never fought against one another, but against bulls, lions, or venatores ( hunter-gladiators ) helped by dogs. It seems that the strongest came from Caledonea ( Scotland ) and Dalmatia. A mosaic fragment from the third century found in a suburb of Rodez representing Caledonian bears that had won renown in circus games preserves the names of six of them: two females ( Fedra and Alecsandria ) and four males ( Nilus, Simplicius, Braciatus, and the champion Gloriosus ). Late in the following century, several letters from the consul Symmachus, prefect of Rome in 381 and 384, recount how this rich and powerful official and upholder of Roman tradition found bears for the circus games: he got them from specialized “recruiters” in Dalmatia, the ursorum negotiators. He worries about a delaying shipment, fearing that during the transport someone will substitute ordinary bears for the remarkable beasts he has been promised and for which he has paid handsomely; finally, he quarrels with the dealers and, for that year, gives up receiving the huge and splendid bears from Dalmatia.

The bear occupied the central place in this bestiary. It was found on banners, helmets, and swords, as well as on belt buckles and metal plates reinforcing breastplates or armor. It was found less frequently on clasps and absent from brooches and jewelry. It played a clearly military role. Moreover, archeological investigation has never uncovered a woman’s jewel or an accessary for a female costume decorated with a bear. For periods preceding Christianization, the bulk of our information comes from abundant funerary material found in tombs. Decorations on various objects show bears entire or just their upper halves. They are sometimes depicted alone, sometimes accompanied or surrounding a warrior, as on the famous Torslunda plate, found on the island of Oland in the Baltic Sea, probably dating from the late sixth century of our era. The two bears are clearly recognizable. Indeed, the same attributes always enable one to identify the animal: clearly marked hairiness; short tail, small, rounded ears; aggressive attitude, and huge paws. The bear is the image of the warrior, or better, the warrior himself, who has decorated his weapons and his armor with the image of the wild beast to take on its appearance, its courage, and its strength. In the sagas, where accounts of dreams are frequent, it is not unusual for a chief or a hero to see a bear in a dream warning him of impending danger; or the bear in an image of a dead guardian ancestor; or else, the hero himself in his dream take on the appearance of a bear to confront his enemies, generally represented as wolves. Narrative traces and uses of insignia come together to bring out the complete assimilation of bear and warrior.

What animal is the one that most resembles man? The answers to this question have varied widely according to time and place, since every society had its own bestiary, taxonomies, and conceptions of the relationship between men and beasts. In Europe, however, in historic times, only three animals have been really considered to be bound by ties of resemblance, proximity, or kinship to human beings: the bear, the pig, and the monkey.